It is important to distinguish between wars of oppression and liberation wars, between imperialist invasion and resistance to it. Anti-imperialist wars create a different consciousness among the population. In early 1942, the artist Sofia Sergeyevna Uranova (1910-1988) was drafted and remained in her division until the end of the war, advancing with it to Germany. For her military valour, Uranova was awarded the Order of the Red Star as well as the medals “For the Liberation of Warsaw”, “For the Capture of Berlin” and “For Victory over Germany”. She experienced shelling, bombing, suffering and the death of friends. This everyday experience became the leitmotif of her art. Uranowa left behind a unique artistic legacy. At the centre of her paintings are people who are certain of their humanity in the face of an inhuman enemy and confident of their ultimate triumph.

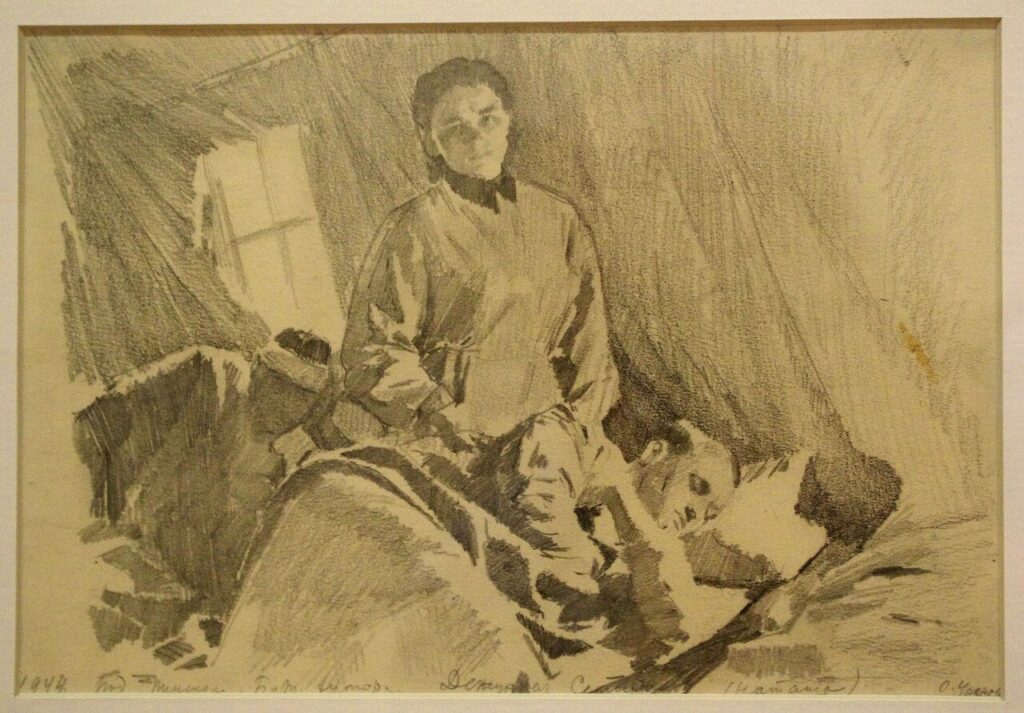

In this 1944 drawing of a field hospital “Nurse on Duty” (In pencil below: Babi Khutor, near Minsk, nurse Natasha), the nurse, in the midst of the wounded, turns her tired gaze towards the viewer. For the moment, the patients are cared for. But all those depicted here will continue to fight, they are by no means discouraged, but are gathering new strength.

The memory of the Great Patriotic War is still alive in Russia and the former Soviet republics today and people still identify with their victory over German fascism. On 9 May, you can see the inscription right down to the smallest village: “No one will be forgotten! Nothing will be forgotten!”

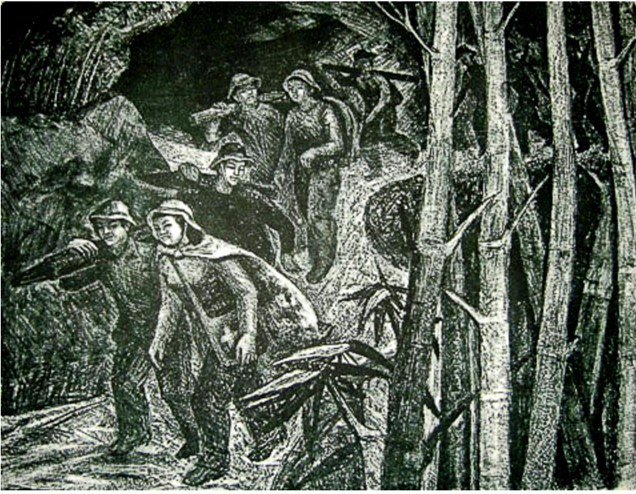

The depictions by Vietnamese artists of their heroic liberation army radiate a similar pride. Here, too, women fought alongside men for their liberation, as Trịnh Kim Vinh (b.1932), depicted in her lithograph “Operation through the Jungle” (1973). Trịnh received awards for her role in the resistance and for her contribution to the art of Vietnam. From 1964 to 1969, she studied art in Hanoi, focusing on women involved in the war effort. She completed postgraduate studies in lithography at the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts (1970-1973) and played a leading role at the Hanoi Art Academy for decades.

In her lithograph “Operation through the Jungle”, Trịnh shows six fighters at night in the dense jungle, with others following from the thicket. The men carry heavy weapons, a woman in the foreground is characterised by her medical bag, another walks behind her. Viewers sense friendship and confidence.

Wars frequently manifest themselves as sanctions and famine caused by the aggressor. The Famine in Ireland was such a holocaust and remains a national trauma. In 1946, Irish artist Lilian Lucy Davidson painted “Gorta” – depicting such colonial-style ‘ethnic cleansing’ that continued to Leningrad, and to Gaza today.

Davidson paints the burial of an infant in a style reminiscent of Kollwitz. The ragged, skeletal figures appear ghostly, close to starvation. Two women and a man are depicted. The woman holding the baby wrapped up in a cloth, probably the mother or grandmother, looks down – the diagonal of her gaze goes over the child towards the spade with which the father will dig the tiny grave. Only the little feet emerge from the cloth. The woman on the other side of the man faces the viewer with her eyes closed – as if she were blind. It is possible that she is the mother, perhaps out of her senses from hunger and despair. It is difficult to tell the age of the three adults, they have suffered too much. The composition is triangular, with the man’s head at the highest point in the centre. He looks directly and unforgivingly at the viewer. Despite his great emaciation, he radiates strength, which runs diagonally from his raised elbow to the tip of his spade. The spade can quickly become a weapon. He will bury his child, but he will not forget anything, and he will take revenge. As in Kollwitz’ plate “Need” (1893/94) or in van Gogh’s work “The Potato Eaters” (1885), the wretched are in darkness. Davidson mainly uses brown earth tones and dark blue. However, the sky directly behind the figures remains bright and conveys a certain glimmer of hope.

What can art do? By engaging with these works of art, we as viewers relate what is depicted to our own experience. We feel our humanity, compassion and solidarity, anger and the will to change the world.