“I live according to the rules ‘visit no one, do not receive anyone’—to which I once added ‘and do not open the peephole on the door for an old woman from Al-Bireh’—and ‘measures, precautions, requirements, and rules.’ Between this and that, I resist and I cook, I sleep, I dream, I sing, and I contemplate, I jump from one safe house to the other. I escape from bad coincidences by virtue of a prayer my mother made nine years ago: ‘Go, my son, may God be pleased with you.’ I get bored and talk to the walls on occasions, I work and feel tired, I laugh and I curse. Before and after all that, my tasks dominate my thinking—my resistance is my life. The self that pushes me toward bad things has fought me and I defeated it, so it fell silent.”

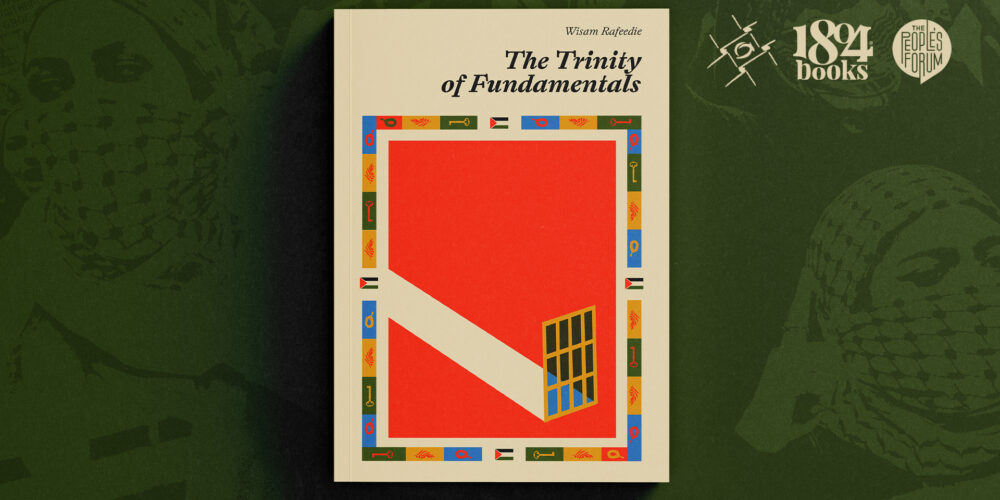

Kan’an, the protagonist of The Trinity of Fundamentals, says this in 1991, as Eastern Europe enters the last phase of the crisis of socialism, the First Intifada enters its second half, and the Gulf sees the aftermath of “Desert Storm”. In the preceding nine years, he saw the Palestinian resistance from a very specific point: one of a professional revolutionary in hiding. Kan’an, a fictionalised version of the author Wisan Rafeedie himself, is a member of the PFLP, Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine. When the party informs him that he is to begin his life in hiding in 1982, adventurous excitement and enthusiasm mixes with his Marxist-Leninist analysis, and he abandons the illusion of normal life under occupation many led — family, university, love. The two pillars of his existence from that point are life and the revolution: we get to see, through internal monologue (or rather dialogue) Kan’an dealing with contradictions and revolutionary analysis taking precedent over some individualist tendencies (“a struggle between reason and nerves”, the author notes). Nevertheless, there remains the constant tension with the missing third pillar, the one to complete the titular Trinity of Fundamentals: love.

The story of Kan’an opens with a knock on the door. The Occupation is pounding on the door, seeking his hiding place. The image evokes the opening of Gillo Pontecorvo’s The Battle of Algiers (1966), but also that of Phil Ochs’ “Knock on the door”: the occupying force is always one ominous knock on the door away from the resistance. The story takes us back to the beginning of Kan’an’s involvement with the Party, and it keeps oscillating between the present moment of the safe house under siege, and Kan’an’s personal history. This history is told with the benefit of hindsight, with constant reflection on material conditions, organising principles, and the historical moment. The author does not shy away from the tone he wrote his Party pamphlets and letters in, offering materialist analysis of the situation, retelling relevant aspects from history of Palestine and PFLP, and citing relevant principles of Marxism-Leninism. Typographical choices give us the voice of the narrator, multiple inside voices of the protagonist (in italics), and the voice of the party (in bold, as seen in the quote at the beginning). In the beginning, the voice of the Party is in the instructions Kan’an receives—it is never othered, Kan’an always insists on being a part of that voice, the part of the collective “we”. At the end of the book, Kan’an’s own words are in bold typeface, as he has become the clandestine printer, the voice of the Party. Coming from a Christian family, Kan’an flirts with a quasi-religious representation of his beliefs, notably with the idea of the Trinity, but also in his loyalty to the party. Through his bearing of the cross, he wouldn’t ask, like Christ, “why hast Thou forsaken me?”, nor would he deny the Party like St. Peter denied Christ as his teacher. Arguably, New Testament motifs here are just one bit of the author’s love for intertextuality and diverse references. The book is full of references to literature (Hanna Mina, Kanafani and Soviet social realists to name a few), Marxist literature, and music that filled Kan’an’s solitude.

Written in and smuggled out of an Israeli prison in 1993, this fictionalised autobiographic account of Wisam Rafeedie’s revolutionary activity in the 80s now appears in English translation. The language of the translation is enjoyable, authentic, and emancipatory—it is the English of the resistance and freedom fighters finding their voice, not one of a colonialist, orientalist voyeur.

The Trinity of Fundamentals, written by Wisam Rafeedie, translated by Dr Muhammad Tutunji, was published in 2024 by the Palestinian Youth Movement, and is available from Connolly Books, Temple Bar, Dublin. Buy here – https://www.connollybooks.org/product/the-trinity-of-fundamentals