On 15 May 2023, an interview with the French ambassador in Ireland titled “Ireland must ‘pull its weight’ on increasing defence” was published in The Irish Examiner. Most of the interview focuses on the perceived need for the European Union to reduce its industrial and energy dependence on other global actors. The ambassador calls for a “level playing field” with China and warns against the European reliance on imports of 5G equipment, electronics, and batteries from China. On the same day, the big American semiconductor corporation Analog Devices announced new investment into their fabrication facility in Limerick, as a part of a strategic EU-US cooperation in semiconductor supply-chain “resiliency enhancement”.

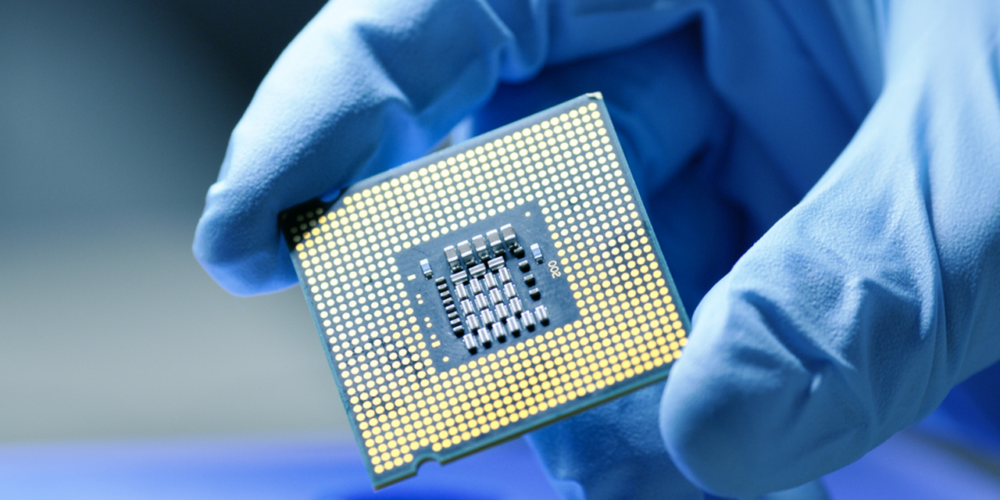

The semiconductor industry is a chain of chip designers and chip manufacturers, delivering microchips used in all modern electronic equipment; from an electric toothbrush to a fighter jet, the chip-hungry markets generate and maintain ever-growing demand for chip supply. Consumers around the world have been experiencing the effects of supply struggling to meet demand since 2020, as the shortage of chips slowed down the auto industry, the computer industry, and other hi-tech sectors. The shortage, widely attributed to “supply-chain disruptions” in an effort to save the grace of the progress paradigm, turned the public attention to East Asia, the region that makes most of the advanced chips put in devices today.

An important part of the US Pacific strategy after World War II was to intertwine the East Asian states into the American supply chains and maintain dominance in an area just off the coast of China and the USSR. Cheap labour and anti-union sentiment were another contributing element, and US military bases sprang up in the vicinity, protecting their interests. Japan was the first to get semiconductor industry deals, and in the 1980s its semiconductor industry made it the world’s second largest economy and a direct competitor to US interests. With a combination of political pressure, industrial pivoting, and shifting manufacturing plans towards South Korea and Taiwan, the US managed to restore domination in the field, but the price for this was paid in creating severe bottlenecks in the design-to-manufacturing pipeline.

Historically, companies that designed chips would manufacture them; however, the “pure play foundry” model of companies like TSMC (Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company, the world’s largest advanced chip manufacturer, holding more than half of the market singlehandedly) where the manufacturer takes care of making the chip and the customer decides on the design, is the dominant mode of semiconductor production today. It has allowed the “fabless” companies like Apple or Nvidia to dominate the hardware world of smartphones and AI, respectively, without making chips themselves and without the need for yearly investments in upgrading the fabrication process. Yearly upgrades, forced by ever-increasing demand and mirrored in the famous Moore’s Law,[1] limit the number of companies able to keep up.

Long seen as a site for the assembly of devices rather than manufacturing their own chips or designing them, China was a secondary player in the American semiconductor game in Asia. With the rise of the Chinese hi-tech companies, Huawei being the most famous example, and the decline of US tech sales in China (with a notable dip after the Snowden revelations), the US intensified its efforts at choking the Chinese ability to participate in the global supply chains. Fully aware that full technological independence is impossible to achieve, and heightening the tensions around Taiwan and its manufacturing facilities, the US proceeded with legislating their trade war on China. Huawei ended up on the US Entity List, preventing the sale of components to the company, and leading to bans of Huawei 5G rollout in US-allied states, as well as the Taiwanese fabrication sites refusing new contracts with Chinese companies. In the most recent US CHIPS Act (2022), State and Defense Departments, as well as companies, receive billions for research, development, and manufacturing costs of bringing the manufacture of chips to the US, while explicitly banning exports of any advanced technology to Russia and China. Europe followed suit with the new EU Chips act (2023). Explicitly citing examples like the European automotive industry, it aims to improve European “competitiveness and resilience” in semiconductor product supply. As should now be clear, it is easy to see that this resilience simply means cutting China out of the game, in what the French ambassador called “levelling the playing field”. The US and its Asian partners maintain their roles in the new European vision of technological dependency.

[1]Moore’s law is the observation that the number of transistors in an integrated circuit (IC) doubles about every two years.