There is nothing more foreign to Ireland than capitalism. While the primitive Irish communist system was not perfect, the feudal and capitalist systems of production were brought to this country by an English bayonet.

The Irish left has struggled to understand this contradiction within Irish capitalism, instead seeing the class struggle as one reduced to the work-place, rather than a class-national struggle with political, ideological, cultural and linguistic forms.

While Marx and Engels finished the Communist Manifesto with the famous call for workers of all countries to unite, it is almost forgotten that in 1921 the Communist International updated that slogan for the new, imperialist stage of capitalism, calling for workers and the oppressed of all lands to unite.

Most of the Marxist-Leninist revolutions in the twentieth century were national in form, for example Cuba, China, Vietnam, Mozambique, Angola. They were no less class struggle in content. The anti-fascist war against the Nazis was called the Great Patriotic War by the Soviet people. There was no contradiction between fighting for the motherland and fighting for socialism.

In Ireland today there is a historical low point in class-consciousness as well as national consciousness. The Irish ruling class has always had an inability to act in the national interest of our people, as can be seen most recently in the fawning over the British monarch. If the bourgeoisie cannot lead the national-democratic revolution, then only the working class can. When Connolly went into the GPO he was not taking a temporary respite from Marxism: he was in fact developing it.

Marxism is not Eurocentric, but Western Marxists are. While we are still a colony awaiting national liberation, we are also very much a part of the West, and this contradiction produces a major weakness in the Irish struggle. While we do owe a lot to the Bolsheviks and the classics of Marx, Engels, and Lenin, Ireland’s liberation also has much to gain from national-liberation Marxists, such as José Carlos Mariátegui, Amílcar Cabral, and others.

Even today there exist the remnants of that ancient Irish system. For example, commonage land in Ireland is land that is commonly owned or, in modern times, owned by the state and rented to grazers. There are just over 1 million acres, stretching from Co. Donegal down to west Cork. The lands are mostly in hilly, poorer areas and are not eligible for EU grants under the Common Agricultural Policy. They are also more common in Irish-speaking areas.

The Irish word meitheal refers to a work group that works in common, such as communities in Irish-speaking areas coming together to take in the harvest.

In other words, socialism is far from being a foreign import. It was capitalism and colonialism that devastated the Irish language. Even many radicals have internalised the colonial attitudes forced on us. How often have we heard that the problem with Irish is the way it’s taught in schools?—almost as if other school subjects, whether English or maths, were taught any differently in what Pearse referred to as the “murder machine” of the education system.

Irish may be a hard language to learn—no language is easy—but then Marxism is itself a very hard theory to master! We shouldn’t take this to mean that we can bring socialism to Ireland just by defending the Irish-speaking community or anything like that but instead that the cultural struggle has an important part to play. Just as it was instrumental in the development of capitalism, it has a part to play in the struggle for socialism.

Caomhín de Barra writes in his book Gaeilge: A Radical Revolution (2019) that “the poorest people in Ireland in the 18th century were Irish speakers, while the people with wealth, political power and social influence were English speakers.”

The Catholic Church was one of the greatest obstacles to the left in this country. The Church was an ally of colonialism; the famous “hedge schools” taught in English; the university at Maynooth did likewise. No wonder, then, that the counter-revolutionary Free State relied on the Church to keep it in power; and the Church’s rule was in many ways almost colonial in the way it conducted itself.

While the Church’s influence has been severely weakened, it has largely been replaced by liberalism, with the demand for national sovereignty curtailed lest it offend the EU. This shows how the left has made a major mistake by leaving this ground for far-right groups to occupy. Dimitrov criticised those who opposed fascism through what he called a “national nihilism” rather than an anti-fascist patriotism.

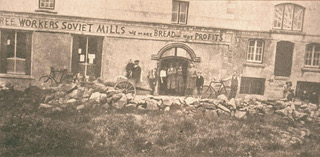

The Easter Rising could not have happened without the national revival, which was itself an indirect product of the Land War. Without the Rising we wouldn’t have had the Limerick Soviet.

As the CPI agreed at our recent national congress, we need to put the national content back into the class struggle, and the class content into the national struggle.