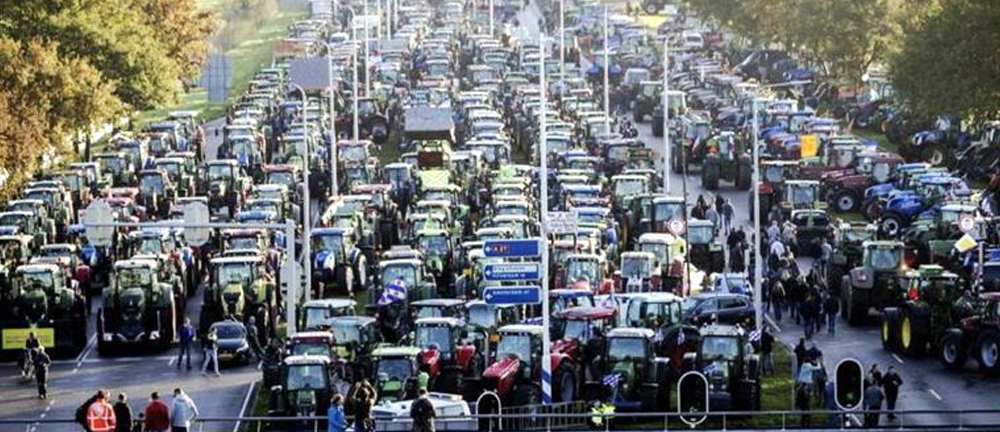

Farm vehicles blockading motorways, burning haystacks on hard shoulders, and heaps of manure at the house of parliament—these images from the farmers’ protests in the Netherlands have been broadcast around the world.

The recent reports of nitrogen excesses, and the magnitude by which it needs to be reduced, have struck a chord with many farmers. Listening to the plenitude of interviews with, especially, cattle farmers, it is clear that they feel their business and way of life are under threat. Farms that have been handed from parent to child may need to scale down or close to meet emission targets. They do not trust the political elite and their directives. Above all, they are seeking respect for the role they play in food production, innovation, and the national economy, rather than being seen as the ravagers of nature.

Reactionary political parties have recognised an opportunity in the discontent and make every effort to shape it to fit their conservative nationalistic agenda. They preach to willing ears that the nitrogen crisis is made up, that it is a ruse to disown farmers and turn their green pastures into concrete towns and cities to facilitate an endless stream of migrants and refugees.

In response, calls are raised from centrist parties for a laissez-faire approach and leaving nature to the farmers, not ensnaring them in a web of government regulation.

This is a dangerous development that provides no solution for the reality of the problems and ignores the harsh truth that the farmers have been left to fend for themselves in a capitalist market economy.

The European Union’s Common Agricultural Policy has driven the concentration of land and capital in agriculture to an immense scale. The goal is to strengthen European capital by exporting food and competing with foreign farmers. By this policy, the majority of agrarian production now takes place in large capitalist agricultural corporations. The immediate victims are the small-scale family farms, which, with diminishing profit margins, have the choice between bankruptcy and intensifying their production, for which banks are more than happy to issue yet another loan.

This development can clearly be seen in statistics. Over the past twenty years the number of cattle and pigs in the Netherlands has remained relatively stable, at 3.9 million and 12 million, respectively. The number of cattle farms, however, has halved, from 45,800 to 22,930, while the number of pig farms has been decimated, from 14,520 to 3,290. This process has taken root in Ireland as well.

The greater part of this production, however, is not for the domestic market. Fed with imported fodder, the intensification has allowed the Netherlands to become the world’s second-largest exporter of agricultural goods, topping €100 billion in 2021. A fifth of this is accounted for by animal products, their waste being the main source of nitrogen pollution. The effects of excess nitrogen in nature have resulted in a diminished biodiversity, where only flora that tolerates elevated levels, such as nettles and blackberries, can thrive. The resulting acidification poses a problem for snails, insects, and eggs, which struggle to maintain their calcium-based skeletons and shells. While this was foreseen as early as the 1990s, Dutch liberal politicians have opted to ignore it in favour of votes and profit.

At the end of this development the farmers are now presented with the bill for the everlasting drive towards industrialisation and intensification that they are coerced into by a government that fails to recognise their role. As the Netherlands is a front-runner in agricultural development, it is there that we see the cracks in the system most evidently form. Let it serve as a warning for us to avoid and learn from.

Should it not be our goal to commonly find a solution, to reach for a sustainable and livable world that seeks to strike a balance with what we require to sustain ourselves and what the world can provide without lasting damage? We must end ruthless competition with farmers abroad and reduce pollution in transport; and therefore production and consumption cannot be continents and oceans apart.

Most farmers recognise the damage done to the world and the very ground they till by over-exploitation but see no way out. They must be helped to escape the endless cycle of diminishing profit margins and a single-minded focus on industrialisation.

To achieve this we require a revolutionary change in the political-economic system, for we cannot entrust a solution to the short-sighted profit-driven decisions of a few entrepreneurs. We require a society that does not revolve around the profits of a few mega-corporations but where the agrarian industry can work to meet the needs of the people. Such a world can only exist with communism.

Notes:

- Communistische Jongerenbeweging [Communist Youth Movement of the Netherlands], “Boerenverzet of reactionaire beweging?” (https://tinyurl.com/4jy3ksb5).

- Statline, “Landbouw; gewassen, dieren, grondgebruik en arbeid op nationaal niveau” (https://tinyurl.com/y4tp8mbc).

- Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek [Central Statistics Bureau], “Landbouwexport in 2021 voor het eerst boven de 100 miljard euro” (https://tinyurl.com/44rm52u8).

- Kevin O’Sullivan, “Census confirms record numbers of cattle on Irish dairy farms,” Irish Times, 10 December 2021 (https://tinyurl.com/yt7ke3vy)