Part 1

I believe that what can give coherence to cultural, political, and ideological work is a definition of the ideology of the Cuban Revolution.

Our ideology is based on the guiding principles of Cuba’s national liberation and social emancipation processes; on the development of our own thought characterised, as pointed out by José Martí, by placing universal thought within a relative, singular context, according to the specific demands of Cuba’s reality.

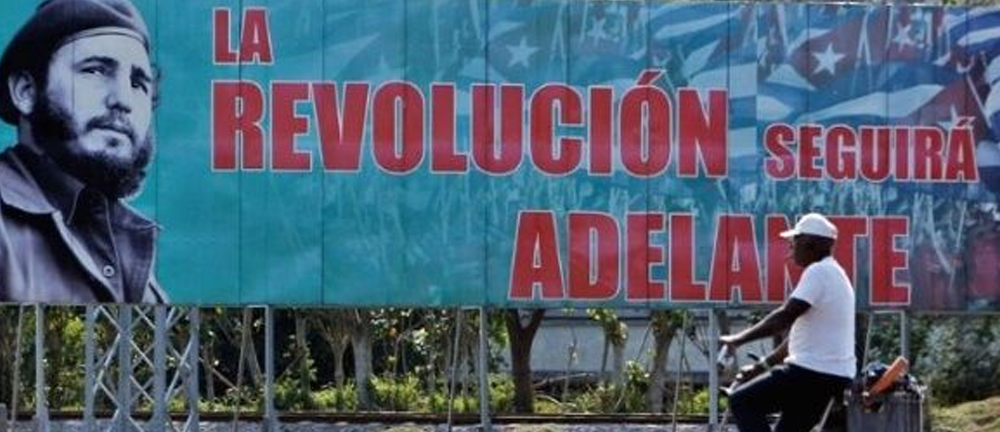

Fidel Castro, deeply knowledgeable of Martí’s thought, was the architect of the Cuban revolutionary project and the person who gave it, in praxis and in his dialectical thought, both universal and particular content. As he stated, his contribution to revolutionary theory was uniting Marxist thought with Martí’s. It follows that the Ideology of the Cuban Revolution contains two guiding components: Cuban revolutionary thought and Marxist thought, adapted to our reality.

This combination is absolutely necessary to understand Cuba’s historical processes and current complexities, as well as those of Third World countries, which have evolved in a manner very different from that of countries in the First World. While the latter is is the centre of developed capitalist modernity, the former constitutes the periphery, the modern world’s marginal areas.

This implies a complexity emerging from the domination and exploitation by imperialist countries which characterise sour historical evolution and the current struggles we face.

In this regard Karl Marx writes in a letter to the Russian magazine Otechestvennie Zapiski, addressing N. K. Mikhailovskiy’s attempt to schematically extrapolate contents of Capital to the Russian reality: “At all costs he wants to convert my historical sketch on the origins of capitalism in Western Europe into a philosophical-historical theory on the general trajectory to which all peoples are unavoidably subjected, whatever the historical circumstances that affect them, to finally take shape in an economic formation which, along with an expansion of the productive forces, of social labour, ensures the development of man in each and every one of its aspects. (This shows me too great an honour and, at the same time, too much contempt.)”

The characteristics of Cuban society and its evolution are based on elements very different from those of Europe and the United States, since our lot was coloniser -colonised, slave holder-enslaved, producer of raw materials within the north-south and east-west commercial network, according to Martí, “the fulcrum of America.”

The study of this complexity and the evolution of Cuban revolutionary thought allow us to understand why in our country, an uninterrupted process of national liberation and social justice has unfolded, and converged in socialism as a consequence of class, social and ideological struggles.

The component added by Martí differentiates this socialism from that of Eastern Europe, by introducing typical Latin American contradictions and paradoxes, as well as the humanist aspect, flowing from its confrontation with capitalist factors that structured a slave society, and later, a society that was dependent not only economically, but culturally, as well.

Lenin would call the Spanish-American War the first imperialist war. Martí, who knew the United States well, understood that Cuba would be decisive in the birth of US Imperialism, and devoted all the power of his thought and action by producing in our country the foundations of world equilibrium: “an error in Cuba is an error for America, an error for modern humanity. Whoever rises up for Cuba today, rises up for all time.”

With regard to Marxist thought, it should be noted that this theory includes three parts: historical materialism, dialectical materialism and political economy. When communicating Marxist ideas, it is important that the concept of political economy is not an economic technicality, but a vision, a method and an essentially political concept.

As far as historical materialism is concerned, it is an essentially theoretical-philosophical analysis that should not be confused with historical science, which, like all sciences, is governed by and evolves on the basis of rigorous methods and factual investigations to ensure the best possible understanding of reality. Scientific findings produce debate and abstractions that penetrate into meta-historical fields.

A fundamental concept guiding the study of specific societies is that of socio-economic formation, created by Marx, which allows the understanding of a specific economic and social complex, with an objective assessment of differences (like those between the Soviet, Chinese, Vietnamese and Korean models as compared to the Cuban, considering their historical, cultural and social evolution).This is essential to understanding contemporaneity and the richness it possesses. Even beyond the base-superstructure scheme, which Marx himself used so effectively, but should not be used casually—as is the case with any binary hypothesis. The essential feature of social-economic formation is the interrelation and interdependence of all components of a specific society, hierarchically established, to configure its unique characteristics (Engels’ parallelogram of forces) Cuban complexity thus acquires cognitive coherence.

Another important aspect is that of the class struggle. It is absolutely necessary to study at first hand the characteristics of social classes and class struggles in a specific society.

In the case of Cuba, its history is linked to the presence of slavery, in its diverse modalities -ranging from patriarchal to intensive plantation slavery – and from this to a society that replaced legal slavery with racial discrimination.

The structuring of republican society further complicated the issue of social classes. To understand this complexity, one must not only consider a class in and of itself but also intra-class divisions, among which is the racist division within the same social class.

Likewise, the influence on ideology of tastes and fashion that affect middle classes, fundamentally, which, in countries like ours, are often more a half-class than a middle class, must be taken into account.

Lenin contributed two fundamental elements to Cuban ideology: the study of the imperialist phase of capital at its birth and the state-revolution relationship, which addresses the structures of power and explains the emergence of revolutionary situations at the beginning of the twentieth century.

Marxism as revolutionary theory and practice, as well as Lenin’s contributions, must confront the current stage of capitalism—considering, for example, the difference between financial capital and speculative capital or neoliberal domination under alliances of capitalist powers which can overcome a period of inter-imperialist war.

Mastery of Marxist and Leninist theory, methods and concepts is fundamental to providing theoretical coherence to the Cuban Revolution’s ideology. Concepts that have been surpassed must be set aside, and experiences, new knowledge, contributed during the 20th century, and the 21st thus far, must be integrated.

Our ideological tools must be up to the task in current debates with new proposals being made, including the lessons learned through our experiences and the development of a political consciousness that has in José Martí and Fidel Castro its most profound and realistic creators.

■ Part 2 will be published in the May issue.