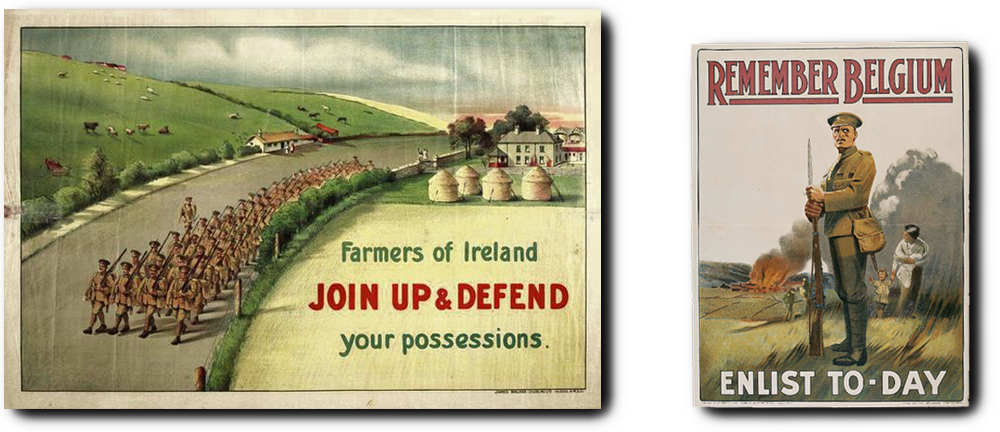

“Gallant little Belgium must be saved from the swinish Hun” was the cry in 1914. So intense was the propaganda deploring and berating the Kaiser’s Germany, and so heart-rending the story of a small European country being violated, that millions enlisted to fight and to die. Among the fallen in “the war to end war” were 50,000 Irish, many of whom were encouraged to join up in order to secure freedom for small nations.

The reality of the situation was qualitatively different, though. The Great War was in fact a struggle for imperial supremacy. Even little Belgium was not so pure after all, with its barbaric, genocidal behaviour in Congo.

Although more than a century has passed since that conflict ended, it is worth reflecting on, if only because those who do not learn from the past are doomed to repeat its mistakes. This is important when analysing current events in eastern Europe. The war in Ukraine is bloody, brutal, and an affront to civilisation. What it is not, though, is a straightforward battle between good and evil, between a plucky little David and a dictatorial Goliath, where outside intervention is based purely on humanitarian considerations.

It goes without saying that people fleeing from the ravages of war deserve assistance and refuge. By the same token, those who offer such help are worthy of acknowledgement. Yet, just as with gallant little Belgium, there is more to the conflict in Ukraine than mere Russian expansionism.

To get a proper picture it is important to put what is happening in context; and, as so often, the economic determinant is vital. With the collapse of the Soviet Union and its European allies, two crucial elements emerged over the following decades. On the one hand, the United States assumed the role of single global superpower or empire. Secondly, with huge numbers of skilled eastern European workers suddenly becoming available, the price of labour fell, encouraging American and western European employers to offshore production. The incentive for these companies to outsource manufacturing accelerated as Chinese facilities became available.

The result was increased profits for American-led finance houses but at the cost of surrendering manufacturing advantage, mainly to China. Inevitably, the balance of economic power has begun to shift in favour of China, aided by its huge and educated population.

Alarmed at this prospect, and in order to resist the Chinese advance, the United States and its allies (dependencies) resorted to old-fashioned protectionism. Hence the ban, for example, on the use of goods and services manufactured by Huawei.

In spite of these trade barriers, China continues to expand its economy and, with it, its global influence. A crucial element in this process is China’s unhindered access to raw materials available through its near neighbour Russia. Moreover, a close alliance with Russia helps secure China’s western frontier, not to mention admission to a very large market.

It takes little imagination, therefore, to guess why the United States and its allies (dependencies) would seek to destabilise this arrangement by whatever means available. It is in this context, therefore, that the question of Ukraine’s membership of NATO should be viewed.

With good reason, Russia is extremely sensitive to any potential threat on its western borders, 2,000 kilometres of which it shares with Ukraine. The horrors of the Second World War are still within living memory, after all. That NATO’s expansion eastwards would cause grave concern in Moscow has never been a secret, or something that Washington is or was unaware of.

Among many senior US policy-makers urging caution, the creator of the “containment of the USSR” strategy, George Kennan, famously described the expansion of NATO into central Europe as “the most fateful error of American policy in the entire post-Cold War era.”¹

In spite of this realisation, when Ukraine’s new president, Volodymyr Zelenskiy, approved a national security strategy in September 2020 “with the aim of membership of NATO,” the alliance refused to reject the proposal or to guarantee neutrality. Instead NATO arms manufacturers supplied Ukraine with a vast arsenal of sophisticated weaponry.² That the Kremlin would respond to this situation was as inevitable as day following night; and, as we now know, it broke international law and invaded.

As a consequence, the United States has been able to rally its allies (dependencies) and lead an enormous hostile campaign against Russia. A media storm has been generated to demonise Russia, sanitise Ukraine’s shady relationship with far-right elements, and rehabilitate unsavoury regimes in Poland and Hungary.

Trade sanctions have been imposed on Russia, which also have the effect of freezing commercial relations with western Europe in particular. Significantly too, China has been threatened with economic consequences if it offers support to Putin.

Only the wilfully blind could fail to see how useful this conflict is proving to be in shoring up Western imperialism in general and US interests in particular. Whether this objective is sustainable in the long run is another question, but for now it will endeavour to maintain the US-led position.

And maintaining position is also uppermost in the minds of the Irish ruling class as it engages with this issue. Notwithstanding the fact that the 26-County state is a minnow on the global stage, the Dublin government has been aggressively supportive of the West’s position. Not only is it leading the campaign to have Ukraine admitted to the European Union but the South’s governing coalition is openly discussing formally ending neutrality. This latter issue is particularly odd, as Ireland’s global military capacity can only ever be insignificant.

One very likely explanation for this new-found enthusiasm for military adventurism is a calculation that the long-standing status quo in Ireland is under threat. A well-documented housing crisis, and a disgraceful two-tier health service starkly illustrating a society of gross inequality, are crying out for fundamental change.

There is also the ever-present matter of an increasingly endangered partition. Sinn Féin riding high in opinion polls is evidence that many are no longer content with the way things are. If covid-induced inflation were to cause workers to seek an even more radical solution than what is being offered by parliamentary republicanism, wouldn’t it be great for the ruling class if it were able to call upon NATO, or PESCO, to save the day for capitalism.

Just think for a moment of how powerful would be the image on RTE of a virus-free Micheál joining Leo at Woodenbridge to wave young men off to fight in a conflict that certainly would be the war to end all war.³

To avoid that scenario, there is a great and immediate need to fight for Irish neutrality.

- Office of the Historian, US Department of State, “Kennan and containment, 1947” (https://history.state.gov/milestones/1945-1952/kennan).

- See North Atlantic Treaty Organization, “Relations with Ukraine” (https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_37750.htm).

- On Sunday 20 September 1914 John Redmond spoke to a meeting of the Irish Volunteers at Woodenbridge, Co. Wicklow, and urged them to join the British army and fight for the empire in the World War.