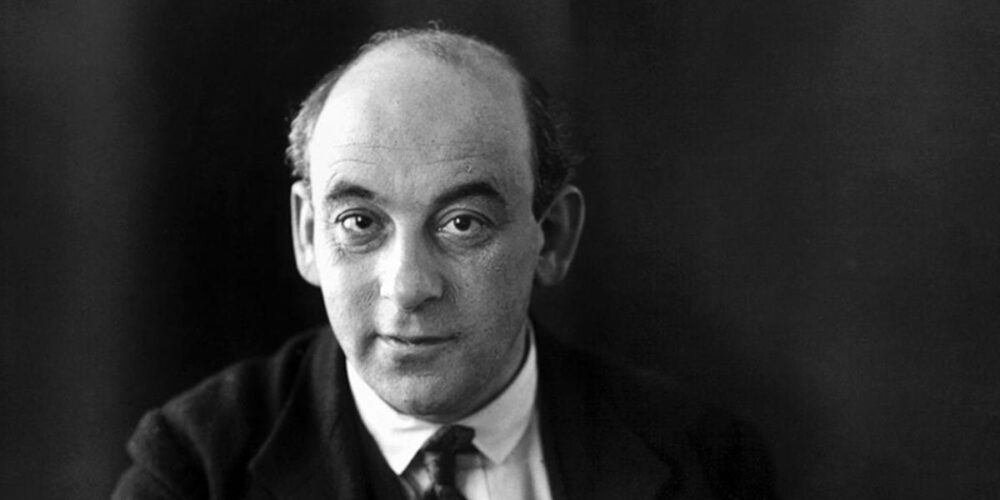

Victor Klemperer is remembered for his seminal study of the language of the Nazis. Born the son of a rabbi on 9 October 1881 in Gorzów Wielkopolski, Poland (then called Landsberg an der Warthe in German), Klemperer grew up in Berlin, where he was baptised as a Protestant. In the First World War he volunteered for the front.

With the rise of German fascism he was declared a Jew. He lost his professorship and his home, had no access to radio, newspapers, or libraries, and could not publish or go to the cinema or theatre.

After the war Klemperer supported socialism as an anti-fascist new beginning. Having fled Germany after the Dresden bombing of 13/14 February 1945, he returned to Soviet-occupied Dresden after the war and was reinstated as professor. He joined the Communist Party, “because he wanted to finish with the Nazis for political reasons.”

Klemperer kept a diary, and after the war he published LTI: Language of the Third Reich (available in English). A keenly observant middle-class scholar, Klemperer grasped how the fascists’ language expresses their inhumanity. In the anecdotally written LTI, Klemperer deals with the central terms of this Newspeak: “Mein Kampf . . . fixed the essential features of its language. Following the Party’s ‘takeover’ in 1933 the language of a group [took] hold of all realms of public and private life.”

Klemperer never identified as Jewish, even after twelve years of fascist persecution. However, fascist racism towards Jews occupies a central place. He draws attention to what was new: “embedding the hatred of the Jews in the idea of race . . . Displacing the difference between Jews and non-Jews into the blood makes any compensation impossible, perpetuates the division and legitimises it as willed by God.”

Concern about postulating Jews as a separate people and its implications appear in a diary entry for 8 January 1939: “It seems complete madness to me, if specifically Jewish states are now to be set up in Rhodesia or somewhere. That would be letting the Nazis throw us back thousands of years . . . The solution of the Jewish question can only be found in the deliverance from those who have invented it.”

In LTI, Klemperer reflects on one aspect of fascist conspiracy theory: “The adjective ‘jüdisch [Jewish]’ . . . [binds] together all adversaries into a single enemy: the Jewish-Marxist Weltanschauung, the Jewish-Bolshevist philistinism, the Jewish-Capitalist system of exploitation, the keen Jewish-English, Jewish-American interest in seeing Germany destroyed.”

Though Klemperer himself was critical of communism until the end of the war, he did have communist friends and describes the fate of communists in the hands of the fascists. “The garden of a Communist in Heidenau is dug up, there is supposed to be a machine-gun in it. He denies it . . . he is beaten to death” (15 May 1933).

An interesting observation is that Hitler and his supporters presented the “Führer” as the new saviour: “The LTI was a language of faith because its objective was fanaticism . . . [although] national Socialism fought against Christianity in general and the Catholic Church in particular . . . the first Christmas after the usurpation of Austria . . . [celebrates] the ‘resurrection of the Greater German Reich’ and accordingly the rebirth of the light . . . the sun and the swastika, leaving the Jew Jesus entirely out of it.”

War is similarly cloaked in Christian terminology. War “became known as a ‘crusade,’ a ‘holy war,’ a ‘holy people’s war’.”

Occasionally Klemperer concentrates too much on the person of Hitler as a “madman.” One finds little about the larger connection with the social system, capital and the economy.

Klemperer gives examples of the renaming of thousands of localities. Parallels with the anti-communist renaming of places after the annexation of East Germany are striking. In East German subculture the GDR names of certain streets, squares and towns continue to be used in protest: Dimitroffstraße, Leninplatz, Karl-Marx-Stadt.

Klemperer’s observations on “Europe” also resonate with contemporary readers: “the ideas of the occident that are to be defended against the forces of Asia . . . For Europe is now no longer simply fenced off from Russia—whilst also laying claim to large areas of its land as part of Hitler’s continent by right—but is also at loggerheads with Great Britain.”

This links to the right-wing extremist language of contemporary Germany, their slogans about “Fortress Europe” as a bastion against the “Great Replacement.” Björn Höcke, an AFD politician, has referred to “the so-called immigration policy, which is nothing other than a multicultural revolution decreed from above . . . the abolition of the German people.” Höcke’s hints at a conspiracy theory have roots in the Jewish conspiracy mentioned above. Such “race-mixing,” it is implied, would destroy the “civilisation” and “identity” of the natives. Conspiracy theories create fear, and present a chilling image of the enemy.

As in Nazi language, today’s neo-Nazis semantically recast everyday terms: “homeland” and “culture” are given racist undertones. It is only a small step to racial violence.

In linguistics, framing is a technique whereby two different things are associated. Where refugees are compared to natural disasters, such as a “tsunami,” or “flood,” this portrays refugees as undesirable disasters, ultimately life-threatening. Another example is the framing of refugees with “security.” It is ultimately about “us” against “them.”

Some of the linguistic strategies mentioned here, such as framing, are adopted by the establishment media. Klemperer pointed out how quickly this language and, therefore, thinking spreads in society.