Born 450 years ago, on 29 September 1571, Caravaggio lived during the Counter-Reformation. The art form of that time, with a specific political function, was the Baroque.

The development of the new middle class—the bourgeoisie—brought with it the dawn of the modern, capitalist era. The artistic expression of this new era of middle-class confidence was the Renaissance. The Reformation was its religious expression.

This new class needed to legitimise its claim to political power at all levels. Protestantism replaced the strongly hierarchical feudal Church with one that did away with the middlemen structures. This reflected the new thinking that challenged the established political hierarchy and aspired, theoretically at least, to political power for all.

The Reformation had forced Catholicism to retreat in many parts of Europe. However, outside Britain no successful bourgeois revolution consolidated the growing economic power of the middle class that would have eliminated feudalism. Instead feudal absolutism emerged. The nobility remained the ruling class, although increasingly capitalist forms began to shape economic life.

The Counter-Reformation was the mainly political and military actions of Catholicism, between 1555 and 1648, aiming to reverse the conditions created by the Reformation in central Europe. Its leading force was the Jesuits. The Counter-Reformation led to the resurgence of Catholicism, to significant shifts in political power in Europe, and to the reclamation of Austria, Bohemia and Poland for Catholicism.

The Counter-Reformation and the Baroque went hand in hand. If the Renaissance had been a violent time, the Counter-Reformation was even more so.

The arts reflected the disparate character of this age. However, an unprecedented class differentiation in art developed. In addition to the ruling culture of the nobility, bourgeois-democratic and upper middle-class forms of culture evolved. While the interests of the upper middle class, associated with the nobility, are reflected in the Baroque, democratic tendencies were expressed in realist works of art.

In 1591 a young painter from northern Italy came to Rome. His name was Michelangelo Merisi, but he took the name Caravaggio from his birthplace.

Caravaggio revolutionised art in Europe. His sense of reality, his this-worldly sensuality, re-established and further developed the realism of the early Renaissance.

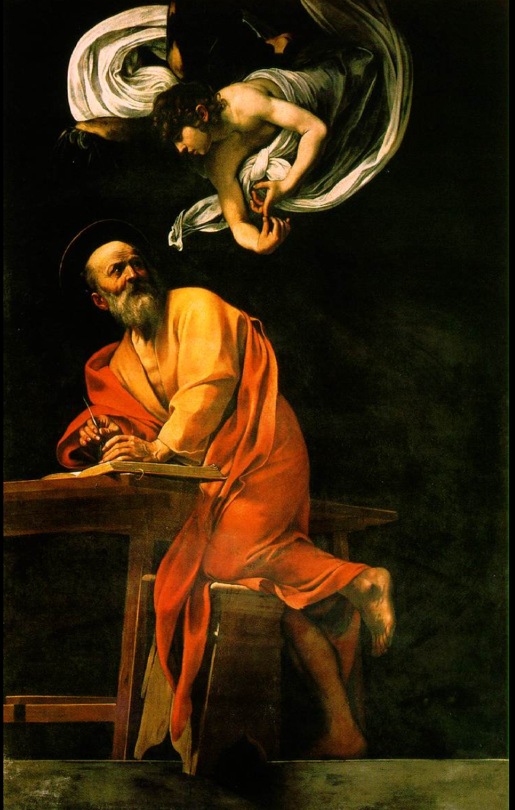

Caravaggio’s painting St Matthew and the Angel (1602) was intended for the main altar of the Cappella Contarelli in San Luigi dei Francesi in Rome. It is a picture that famously exists in two versions.

In this first painting, St Matthew is dressed in short workman’s clothes, leaving his arms and legs bare. His legs are crossed, and his left foot almost breaks through the painting at the point where a priest would hold up the host at Mass. To make matters worse, Matthew is flat-footed, with dirt under his toenails.

He seems to have difficulty writing, his hands unused to holding the quill as he peers at the pages; even his writing appears too big. The angel helps him to write the Gospel. The viewer looks on the scene from above.

The clergy rejected Caravaggio’s interpretation of the saint as an illiterate peasant and objected to the intimate relationship between the apostle and the angel holding his hand. He had to paint a second picture.

This is less realistic. Matthew is biblically dressed and towers above the viewer. The angel hovers over him, there is no physical contact, and Matthew writes by himself.

Caravaggio’s sense of realism stood in the way of painting idealised forms. His real-life models came from among the ordinary people; these were the people who mattered, who life was all about, as far as Caravaggio was concerned.

Caravaggio worked mainly for the Roman clergy. Consequently, most of his works have a religious theme, yet they are profoundly humanist. This painter rejected the highly ornamental, empty and often triumphalist Baroque manner. He painted everyday reality, the ordinary people he encountered on the streets of Rome, including the most deprived: beggars, prostitutes, criminals. Even his religious paintings are always linked to the violence and deprivation Caravaggio saw all around him. He was unwilling to look the other way.

This is the life we encounter on Caravaggio’s canvases; this is his time that he could not escape from. Life around him was full of pain, and Caravaggio’s insistence on realism emphasises this; and for that reason he cannot be counted as a Baroque painter. The realists of the following centuries could justifiably refer to him.

When Caravaggio killed a man in a quarrel on 28 May 1606 he was forced to flee Rome, and he spent the rest of his life on the run, spending time in Naples, Malta, Messina, and Palermo, leaving behind masterpieces that lastingly influenced seventeenth-century European art.

Caravaggio died in exile, soon after arriving in Porto Ercole, on 18 or 19 July 1610, aged only thirty-eight, and was buried in an unmarked grave.