Last month Kathy Sheridan, writing for the Irish Times, opined about the dilemma faced by Ireland’s middle class as they agonise over whether or not to vote for Sinn Féin. The problem, it would appear, relates to the fact that while the party is promoting progressive policies, it simultaneously glorifies what the writer describes as “killers.”

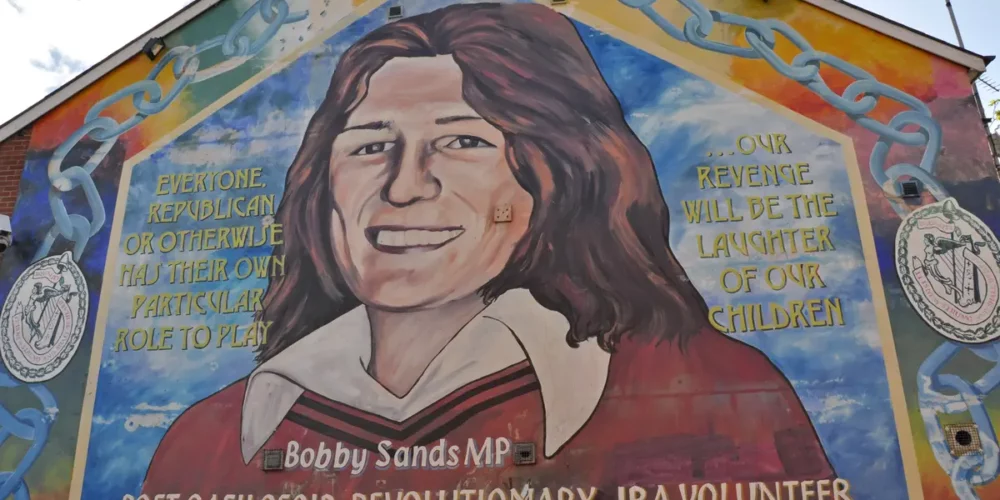

Sheridan described the case of a well-educated young man who has publicly declared his intention of joining Mary Lou McDonald’s organisation, notwithstanding the fact that Sinn Féin is unapologetically commemorating those who died on hunger strike.

It would seem that there is concern that a section of Irish society that has voted for Fine Gael and its predecessor since the foundation of the state might be seduced by Eoin Ó Broin’s critique of government housing policies. Having spoken fondly for years of how Grandpa used to canvas for Kevin O’Higgins, innocent middle-class youngsters may now elect people who once supported the use of armed force.

Nor is Sheridan alone in drawing attention to the alleged discrepancy between Sinn Féin’s current activities and the policies it promotes. The minister for justice, Heather Humphreys (Fine Gael), recently accused the Shinners of hijacking history and weaponising it for their own political ends. She was addressing her party’s annual Béal na Blá commemoration for the one-time IRA director of intelligence Michael Collins. In a speech that is beyond parody, she told her listeners that she shared a view of history similar to that of the “Big Fella.”

Telling history to suit one’s political objectives is nothing new, nor is the practice confined to any one party or group. Sinn Féin is not the first to interpret the past to its own advantage. However, that is not the real reason why the party is subject to endless accusations and a constant tirade about its ethics, its past, and its internal organisational structures. Its recent electoral successes have drawn attention to something much more profound than spin-doctoring with the facts of history.

Irish society, north and south, is in a process of transformation. Over the course of recent decades the Republic has introduced legislation providing access to contraception, divorce, same-sex marriage, and abortion. Taken in isolation from other events, these socially liberal reforms would not necessarily challenge the status quo. However, other significant happenings have created conditions and circumstances that are making old fixtures difficult to sustain.

The economic crash of 2010 has had a lasting impact. The extent of system shock took the establishment some time to recognise. In the early days it seemed that the population of the 26 Counties was prepared to passively accept the imposition of austerity and the concomitant neoliberalism. For a period it looked as if the working class would stay silent and meekly pay the gambling debts of Irish and European bankers.

Slowly but surely that position changed. First came the grass-roots movement against household charges. Then came the massive, popular and largely successful movement against the imposition of water charges. Significantly, this campaign was reinforced by support from organised labour. Then, in the arena of parliamentary politics, this period has also witnessed an end of the long-standing two-and-a-half-party system as new faces arrived on the scene.

It was the general election of February 2020, however, that underlined the extent to which old certainties have changed. Sinn Féin achieved a remarkable result, obtaining the largest vote for any single party and in the process forcing the conservative parties of Fianna Fail and Fine Gael into a marriage of convenience.

Most worrying for the establishment was the profile of the Sinn Féin vote: young and geographically well spread, seemingly little concerned with the past and motivated by socio-economic and climate issues.

And then came covid-19 to expose still further the bumbling incompetence of a hapless coalition. Moreover, where the tripartite government did manage a success, it has the effect of raising other questions. There is, for example, the highly efficient, well-run and free covid testing and vaccination service, something that only went to demonstrate the contrast with the iniquitous two-tier health service advertised so often on the state broadcaster.

Adding to underlying instability is the situation in the North. Changing demographics, perfidious British Tories creating a regulatory border in the Irish Sea and, most recently, having its devolved government preside over the worst covid rate in western Europe makes for a deeply unsettled Six-County political entity. It remains a reality that major events in the North can quickly have an impact on the South and possibly even more dramatically now that Sinn Féin is such a significant presence both sides of the border.

In the wider sense, this all raises the question whether Sinn Féin poses a threat to the existing economic and power system or whether it merely challenges the current parliamentary hegemony of the two main coalition parties; hence the relentless pressure from different quarters to try to ensure that the party mellows into the type of conformity long practised by the Labour Party.

Time alone will tell how Sinn Féin develops. What is beyond question, though, is the existence of a new, young and as yet unquantifiable element within Irish society. In fact this is a phenomenon not necessarily confined to Ireland. A recent article in the Financial Times viewed this as an almost global reality.*

While only a newspaper article, the Financial Times comment nevertheless raised an issue that is most probably of concern to the establishment here and of interest to many of us who are not part of the ruling class. It noted that many among the younger generation are losing confidence in the bourgeois parliamentary process; instead they are turning to grass-roots activism devoted to a range of causes, such as the above-mentioned socio-economic and environmental issues.

Although still on a relatively small scale, we saw some evidence of this last month in Dublin. A group of activists from Co. Tyrone protesting outside Leinster House against goldmining in the Sperrins was joined by activists from different parts of Ireland. Noteworthy was the number of young people involved and speaking powerfully; equally noticeable was the absence of representatives from any of the main political parties in either jurisdiction. It was grass-roots activism of the empowering kind.

A sign of things to come? Well, why not?

*“Losing the generation game: Could economic setbacks radicalise graduates?” Financial Times, 24 August 2021.