In what other country would there be web sites offering the equivalent of “funny Irish place-names”?—which in fact are not Irish at all but corruptions. And the great majority of these are not even corruptions in the usual linguistic sense—i.e. changes made over time by the usage of people (in our case colonists and planters) who can’t speak the local language—but invented in cold blood in the nineteenth century by people who did, in fact, know better.

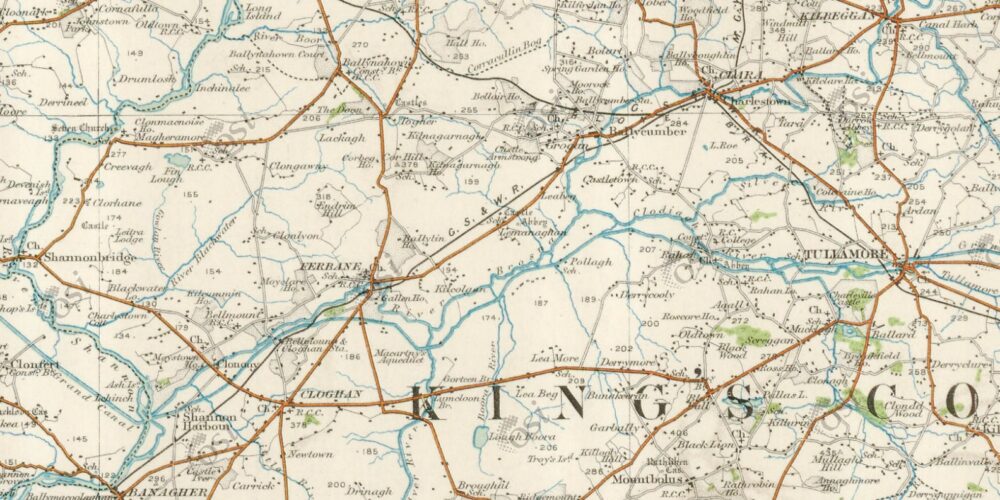

The Ordnance Survey, a branch of the British army, was given the task of surveying the whole country and producing large-scale maps. This they did with great precision, producing maps of extraordinary quality, some of which can still be seen and appreciated today.

In addition, the Topographical [i.e. place-names] Branch of the Ordnance Survey was given the task of recording place-names for printing on the maps. For this purpose the Irish scholars (and they were scholars) employed by the Ordnance Survey compiled a list of officially corrupted components to use when the only names that could be collected from local people were Irish ones, which was the case in the greater part of the country in the 1820s, when the first surveys were carried out.

So, for example, Baile (settlement) was to become “Bally,” while Béal (river mouth) was to become “Bel”; and there were dozens of others. Kill, Drum, Beg and numerous other meaningless syllables were contrived, many of them with an accidental resemblance to English words, prompting the mirth of foolish people.

In this way monstrosities were created that are neither Irish nor English but meaningless and often unpronounceable gibberish, which now litter the countryside on official road signs. So let’s have a good laugh at Mickeen (Co. Galway), or Ballymuckleheany (Co. Derry), not to mention Muckanaghederdauhaulia (Co. Galway).

The gombeenmen and philistines may say, “But I can’t pronounce Muiceanach idir Dhá Sháile!” Well, I can’t pronounce “Muckanaghederdauhaulia,” so we’re quits. And in the first case at least they can find ready assistance—and help to keep the community’s self-respect.

Most authentic place-names describe the landscape, or refer to a mythological figure, or to an Early Christian whose cell became the centre of a settlement and later a town. A comrade who grew up in Grennan, Co. Meath, delights to remember that the authentic name is An Grianán—the sunny place. Who would not prefer to know about, even perhaps to be proud of, such names?

The few campaigns to defend or promote the authentic names are now met with a torrent of abuse as well as active hostility from local gombeenmen, because “the tourists wouldn’t like it.” (The same tourists don’t seem to have much difficulty in France or Germany, or indeed in Wales, where the Ordnance Survey mainly took a different approach; or at least—being, after all, guests in another country—they understand that they have to put up with it.) In some instances the gombeenmen have succeeded in recent years in overturning the authentic name where this had been made the official name.

In a world in which authenticity is now valued, with countries as diverse as India and Canada, not to mention post-colonial countries such as South Africa, reinstating native names, it’s depressing to think that there are Irish people who will go to the trouble of collecting the worst of these monstrosities, then to the expense of setting up a web site, to invite others to laugh with them at Ireland’s sad history and betrayal of its culture.