Albrecht Dürer was born 550 years ago, on 21 May 1471, during the Renaissance, a time of upheaval that rang in the early modern age.

With improved production methods, industry and trade grew rapidly, bringing with them more money and the strengthening of a new middle class. Modern science developed, inherited truths were called into question, and the working people began to challenge their appointed places in the social, political and religious hierarchies. It was a time, among other things, when the peasants arose and demanded to be treated as equals.

The Reformation movement began with John Wyclif in England, continued with Jan Hus in Bohemia, and culminated in Germany. Popular social opposition became part of it. Social forces in religious guise fought the Hussite wars in Bohemia.

As Engels describes it in The Peasant War in Germany, Luther became afraid when he realised the socially explosive effect his challenge to Rome’s hierarchy had on the peasants, who understood this to legitimise aspirations to change their own lot. Luther’s theological reform did not question class antagonisms.

Thomas Müntzer became the leader of the popular opposition. He led the Peasant War, which challenged the old social order. Luther, along with the bourgeoisie, turned against the revolutionary peasants, preventing the unification of all opposition forces and setting back major social change by centuries. The peasants and their urban plebeian allies were defeated; Müntzer was imprisoned and beheaded.

The impact of the working classes on German art of the Reformation period survives in numerous pamphlet woodcuts from the early sixteenth century but above all in the many prints by Dürer and his circle. Dürer‘s influence can be seen in the work of Grünewald, Riemenschneider, Jörg Ratgeb and many other artists and infuses German art of the Reformation period with a haunting popular appeal.

Dürer’s genius so dominated the art of the early bourgeois revolution in Germany that this is known as the Dürer epoch. He was born in Nürnberg, the son of a goldsmith, studied for three years in the workshop of Michael Wolgemut, spent four journeyman years in Basel and Strasbourg, among other places, and finally settled in Nürnberg. Twice he crossed the Alps to Italy, first in 1495, the second time in 1505/06, each time spending an extended period in Venice. A third journey took him to see the Netherlands in 1520/21.

The remarkable portrait of Catherine (fig. 1) was drawn from life during the journey to the Netherlands. It shows the artist’s great interest in people who came to Europe because of growing international trade, including the slave trade. Catherine was a twenty-year-old servant of the Portuguese commercial agent João Brandão, who administered the Portuguese spice monopoly in Antwerp. Dürer was his guest when he travelled to Antwerp in 1521.

It is likely that Brandão acquired this African woman through his trade connections. Her name suggests that she had converted to Christianity. Dürer’s obvious interest here is in the individual person. His deep humanism infuses her portrait with the same dignity he affords the peasants he depicts.

Dürer was the first German artist to capture the peasants’ self-confidence that had been stirring since the late fifteenth century and the first to portray peasants as aesthetic subjects. Through Dürer, depictions of peasants appear in the revolutionary pamphlets of the time.

The wonderful copper engraving of three armed peasants (fig. 2) shows them in serious conversation. They are clearly intelligent and dignified people. One of them carries a rapier, another has a knife in his pocket and spurs on his shoes, all suggesting that they are rebellious peasants; the third figure reaches into his waistcoat, from which he might produce a leaflet.

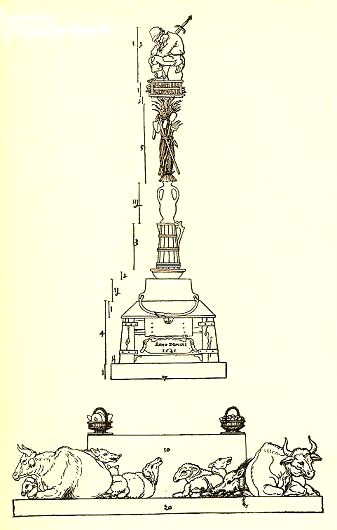

Dürer also set an example during the Peasant War. When Luther turned against the peasants and became the prince’s vassal, Dürer took a stand against him. Luther advised that the princes slaughter the rebellious peasants; Dürer, on the other hand, professed his support for the peasant army with his Peasants’ Monument. In 1525, in the third book of his Unterweisung der Messung (Instruction in Measurement), as a model for the proportioning of a monument he included a woodcut that commemorates the defeated peasants.

The column (fig. 3) shows livestock and household and agricultural equipment from a peasant holding, now the ownerless booty of the conquerors. Instead of the victorious conqueror crowning the pillar there is a peasant, pierced by a sword. We see him in the posture of Christ at rest, the slain peasant as the true follower of Christ.

The Peasant War just over, siding with the revolutionary peasants was far from safe. Many artists suffered persecution. Matthias Grünewald took part in seditious acts, had to go on the run, and died a hunted person. A passionate and rebellious spirit, portraying the representatives of the church as fat, arrogant executioners, inspires Jörg Ratgeb’s main work, the Herrenberg Altar. Ratgeb joined the peasants and became a military adviser. Following the defeat of the peasant army, he was publicly quartered in the marketplace of Pforzheim in 1526. Tilman Riemenschneider, a foremost sculptor of the late Gothic period, a respected citizen of Würzburg and member of the council, was arrested and tortured. He ceased all artistic activity after this.

In the last years of his life Dürer turned away from art to more scientific pursuits. He died on 6 April 1528 at the age of fifty-seven. He remained close to the common people, sided with the democratic movement, and fought for it with the weapons of his art. The greatest artists of that time in Germany stood with the revolutionary people.