George Bernard Shaw wrote: “Keats achieved the very curious feat of writing a poem of which it may be said that if Karl Marx can be imagined writing a poem instead of a treatise on Capital, he would have written Isabella.” The 200th anniversary of Keats’s death this month is an opportunity to celebrate this revolutionary romantic.

The English, American and French Revolutions had hailed the irreversible arrival of capitalism. Conservative governments throughout Europe understood and feared the implications of these revolutions and reacted with an increased suppression of democratic movements. Britain, already a bourgeois society, now feared insurrection by the working class, becoming increasingly repressive itself.

Romanticism is the first expression of the radical self-criticism of industrial capitalist society. In its most advanced writers, such as Shelley, the vision reaches beyond capitalism and supports the first working-class movements.

Byron used his first speech in the House of Lords in 1812 to side with the working people against government tyranny. Keats stands alongside Shelley and Byron against the enslavement and destruction of humanity.

Here are the stanzas Shaw refers to:

With her two brothers this fair lady dwelt,

Enriched from ancestral merchandize,

And for them many a weary hand did swelt

In torched mines and noisy factories,

And many once proud-quiver’d loins did melt

In blood from stinging whip;—with hollow eyes

Many all day in dazzling river stood,

To take the rich-ored driftings of the flood.For them the Ceylon diver held his breath

And went all naked to the hungry shark;

For them his ears gush’d blood; for them in death

The seal on the cold ice with piteous bark

Lay full of darts; for them alone did seethe

A thousand men in troubles wide and dark:

Half-ignorant, they turn’d an easy wheel,

That set sharp racks at work, to pinch and peel.

Keats describes ruthless global exploitation, something we easily recognise today: in mines, in factories, in rivers, and the sea. While these stanzas are unusually direct for Keats, he evokes an aspect that becomes increasingly central to his poetic idea: how the human senses are destroyed in what he refers to as the “barbaric age” of capitalism. He captures and depicts these times as inappropriate to humanity.

“Ode to a Nightingale” describes an unnatural world:

Fade far away, dissolve, and quite forge

What thou among the leaves hast never known,

The weariness, the fever, and the fret

Here, where men sit and hear each other groan;

Where palsy shakes a few, sad, last grey hairs,

Where youth grows pale, and spectre-thin, and dies;

Where but to think is to be full of sorrow

And leaden-eyed despairs,

Where Beauty cannot keep her lustrous eyes,

Or new Love pine at them beyond to-morrow.

Beauty evolves as Keats’s measure for a humane world. A profit-driven society that insatiably pursues money at all costs, including brutal repression and wars, destroys beauty. In a society like this “the Ceylon diver . . . went all naked to the hungry shark; | For them his ears gush’d blood”; and here “but to think is to be full of sorrow.” Yet despite it all Keats shows that beauty arises as human potential, over and over again with every new generation. And beauty is felt through the senses.

For Keats fully realised that human potential means that humans can appreciate the world through their senses. Capitalism destroys these senses: loins and ears gush blood, eyes are hollow, eyes are leaden.

While the reader has to activate mentally all senses to “live” the images, the actuality of this potential lies in the future. The building-blocks exist. Humanity has the ability to experience with all its senses the beauty of a humanised world. In the world as it is, this potential is thwarted: “Beauty cannot keep her lustrous eyes.”

Keats focused his poetics on what defines a truly human world, a place where humans are at one with themselves and their environment. He believed that human beings could develop their full sensual potential only in a world with which they were at one. In the world of nineteenth-century Britain and Europe, this was patently impossible.

Keats explores the nature of this beauty in his great odes of 1819. It is a beauty that is intrinsically tied to life as it should be, where humans and nature are in complete harmony with one another, where beauty is dynamic, changeable, in process, and includes its fulfilment. Beauty is life in tune with itself. It is dialectical, natural, and nurturing. This is Keats’s truth.

Part and parcel of Keats’s understanding of beauty is his programmatic attack on the denial of sensual pleasure by Christian religion. Like Shelley and Byron, Keats saw the reactionary role played by the Christian churches in nineteenth-century revolutionary Europe as intrinsically anti-life. Sensuousness marks Keats’s entire work and inspired artists like Harry Clarke to create the stained-glass window illustration of The Eve of St Agnes at a time when the denial of the physical senses and sexual pleasure was equally suppressed in Ireland of the early 1920s.

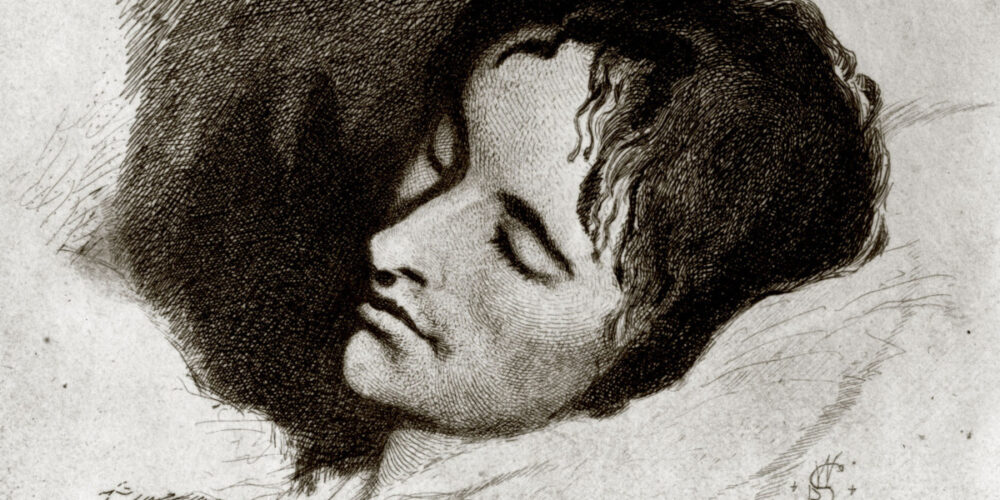

John Keats is one of the greatest English writers; he was a revolutionary poet whose vision reaches far into the future. He died two hundred years ago, on 23 February, aged only twenty-five.

■ Jenny Farrell is the author of Revolutionary Romanticism: Examining the Odes of John Keats (Nuascéalta, 2017), available from Connolly Books (Dublin), Charlie Burns and Kenny’s (Galway), or online.