Understanding imperialism is vital to our understanding of the world today, enabling us to chart a path forward to tackle the environmental crisis and to move humanity towards a system of equality and common ownership—socialism.

Unfortunately, many on the left either reject the existence of imperialism in favour of a mechanical understanding of a capitalism of a different era or reduce imperialism to the military invasions and occupations of certain states or areas. Both views are incorrect.

While capitalism is the system, the process by which capital reproduces itself (M–C–Mʹ and M–Mʹ), imperialism, is the entirety of power structures globally—political, economic, social, cultural, military—that underpin accumulation on a worldwide scale and that have divided the world into a centre and a periphery, north and south.

Our understanding of imperialism as a historical stage of capitalism, the concrete manifestation of capitalism at this point in history, goes back to the work of a number of theorists at the beginning of the twentieth century, when this stage of capitalism was bursting forth, including Hobson, Lenin, Luxemburg, Hilferding, and Bukharin, to name a few.

Marxist theorists, in the tradition of those early critiques of imperialism, are now discussing and defining the present period as “late imperialism,” where global monopolies govern a world system that is crisis-ridden as a result of the very processes of concentration and centralisation that led to these monopolies.

Samir Amin points to a triad of imperialist centres—North America, Europe, and Japan—as being the core. The features of late imperialism are stagnation, globalised production, labour arbitrage, financialisation, permanent global unemployment, permanent military expenditure and war, and privatisation.

These features give rise to a number of crises or rifts, which are irreconcilable:

- economic

- the state and democracy

- ideological

- environmental.

The degree of concentration of economic power has ultimately caused stagnation in the system, resulting in constant bubbles, bursts, and crises of overproduction. The concentration of wealth has caused the decay of democracy in western states and corrupted democracy in the periphery. Democracy is no longer the chosen path of rule for capital as states become increasingly authoritarian, leaving only a democratic façade.

Capital is increasingly turning to nationalist and neo-fascist organisations to govern politically for it, as ideologically it has little to offer, other than reactionary demagoguery, in the context of high levels of inequality, poverty, and permanent unemployment globally.

The final, but most important, element of the crisis of late imperialism is the environmental rift between capitalism and nature. Given the necessity by global monopolies to exploit nature for profit, there is no question but that imperialism will not be able to continue and prevent environmental catastrophe. It is one or the other; and incorporating radical ecology in anti-imperialist strategy is vital for the fight for socialism.

Ultimately, these points of crisis are what call into question the system’s ability to reproduce itself for that process of M–C–Mʹ and M–Mʹ to operate uninterrupted and to manage disconnect within structures. But what is lacking is the agency for turning these crises into a revolutionary movement; what is lacking is a conscious anti-imperialist internationalist global movement, led primarily by the working class but including peasants, agricultural labour, intellectuals, students, and oppressed peoples.

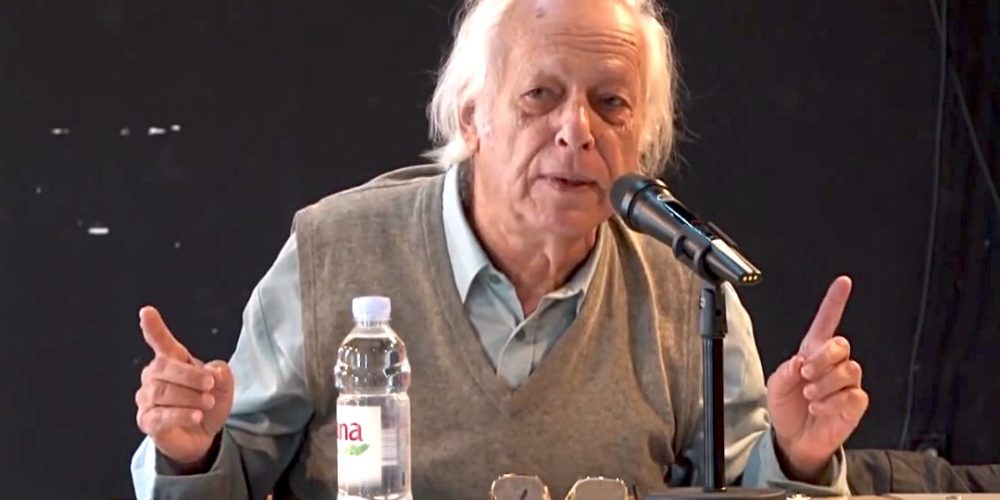

Before Amin died he made a call for this.

Constructing a transnational alliance of workers and oppressed peoples of the entire world has to be the main objective of the struggle to counteract the spread of contemporary imperialist capitalism . . . Nothing decisive will affect the attachment of the peoples of the triad to their imperialist option, especially in Europe . . . The most probable outcome will be a remake of the twentieth century: advances made exclusively in some of the peripheries of the system. But these advances will remain fragile, as have those of the past, and for the same reason—the permanent warfare waged against them by the imperialist power centers, the success of which is greatly due to their own limits and deviations . . . This construction cannot be a remake of the Internationals of the past—the Second, the Third, or the Fourth. It has to be founded on other and new principles: an alliance of all working peoples of the world and not only those qualified as representatives of the proletariat (recognizing also that this definition is itself matter of debate), including all wage earners of the services, peasants, farmers, and the peoples oppressed by modern capitalism. The construction must also be based on the recognition and respect of diversity, whether of parties, trade unions, or other popular organizations in struggle, guaranteeing their real independence.

Amin saw progress as stemming primarily from the peripheral countries and peoples in struggle against imperialism—and the role of progressives in the core countries to be an anti-imperialist support for these struggles and the weakening of core imperialism.

He called for a new International. Right up to his death Amin developed an advanced Marxist analysis, and also challenged us to conceive of how we win socialism, how we make revolution. This call is worth serious consideration.