Over the past two months we’ve been reminded constantly about the supposed health of our economy. Unfortunately, things are not as healthy as cherry-picked statistics might suggest—as anybody looking for a hospital bed or a home can clearly see.

We’re highly vulnerable as a small, open economy to the vagaries of international capital, particularly to problems in the United States. As the 2008 crisis has shown us, issues in the core soon spread to the periphery, and the bursting of bubbles in the United States soon becomes a global issue that affects us all. For this reason it’s worth assessing a number of current weaknesses in the US economy.

Pensions, corporate debt, and equity bubbles

Each downturn has its origins in the “solutions” to the last; and the one that looms before us is no different. Quantitative easing (QE), which involved central banks creating trillions of dollars through the purchase of private bonds and financial assets, was supposed to encourage lending and investment. In one respect it worked. Corporate debt has bloomed to unforeseen levels, though productive investment has failed to increase in tandem, a phenomenon we also see closer to home in the EU.

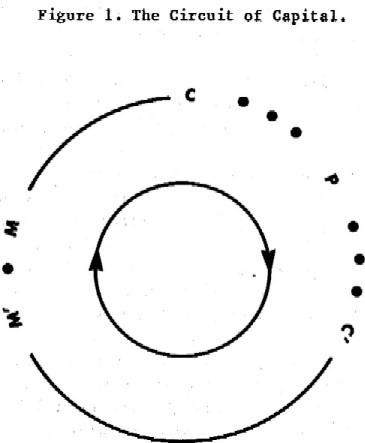

It was assumed that a blockage in the circuit of capital[1], M–C … P … Cʹ–Mʹ rested with M, indicating that the problem lay in a shortage of money capital. But the problem lies rather in the movement from C to P, indicating a crisis of confidence in the capitalist class about throwing their capital into the process of production.

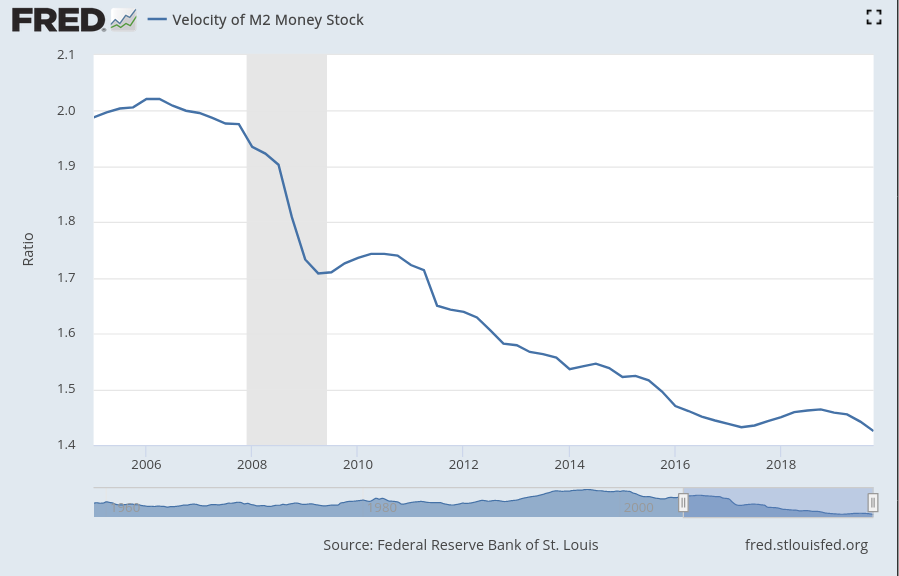

With declining rates of profit and deep uncertainty, there is little incentive for the capitalist class to risk what capital they have now if they are not certain to recoup it later. We see indications of this as the velocity of money (M2) has collapsed[2], indicating that money is being hoarded rather than used productively.

Who bought the corporate debt, and what did corporations do with it if not employ it in the process of production? The purchasers have largely been central banks through QE and pension funds, the latter desperate to buy revenue-generating assets, even if their quality is highly dubious. Money raised through the issuing of corporate debt has largely been used to buy back shares, inflating the value of stocks, to the delight of those who earn their living from ownership rather than labour.

So, once again, the stock market soars while normal people suffer.

Usually there is a significant correlation between the increase in share price and an increase in the value of a corporation. As a corporation becomes more profitable the share value increases, as stock-owners expect higher returns. The link between value and growth in stock price has never been weaker, with share prices climbing to exalted heights as underlying valuations fail to match—the driving factors being share buybacks, recent tax cuts, and bubbles in momentum stocks by pension funds forced to seek high returns because of low interest rates. None of these are sustainable.

This lays the foundation for a crisis in the pension system and the stock market of catastrophic proportions, a crisis that may be significantly worse than the last. Workers are, for all intents and purposes, lending their pensions to the capitalist class, who use the money to inflate the value of their assets—and have no intention of paying those loans back when the scheme inevitably collapses.

Far from stability, we’re teetering on the edge of a very dangerous precipice.

How will it affect ordinary people?

Predicting the exact time and date of an economic crisis is a waste of time. That doesn’t mean that we can’t observe the weaknesses in the capitalist system that are most likely to bring us to the next crisis. Like a ship with numerous breaches and hasty repairs to its hull, we are able to identify the most likely points of failure even if we don’t know the exact moment when a breach will be opened. When the hull starts groaning and small leaks spring, we should take note.

As the last crisis has shown us, the interests of the capitalist class are protected while ordinary people are forced to carry the burden of saving a system that works against their interests.

The establishment will offer the same ineffective “solutions” to the next crisis as it did for the last: more austerity, as ordinary people are swindled out of their pensions and forced to endure cuts to vital public services—none of which will solve the underlying problem of a diminishing rate of profit inherent in the capitalist mode of production.

Yet there is an alternative. Rather than leaving the process of production to the whims of a class hell-bent on accumulating capital, regardless of the social and environmental impact, we can and must organise our system of production around human needs.

The only way to prevent this destructive cycle continuing is to break it, with demands for a democratic, rational economy that plans for, and meets, the needs of the majority.

Footnotes

1.

In Capital Volume 2, Marx moves from an examination of the process of capitalist production to an examination of how capital undergoes a series of circuitous metamorphoses. This occurs in three stages, depending on where one chooses to start the examination of the circuit. The example presented here is the circuit which commences with money capital M – C … P … C’ – M’.

In the first stage of the circuit [M – C] we witness a given amount of money capital (M) which is used to purchase a given quantity of commodities (C), inclusive of labour power and means of production. This is akin to the capitalist who takes €1,000 and uses it to purchase €500 worth of materials as well as €500 to employ labour power. For example we might consider a capitalist who owns a bakery where sugar, butter, gas, ovens and so on constitute the materials employed in production whilst wages constitute the purchase of labour power, which signifies a potential for work.

In the second stage of the circuit we witness the process of production (P). Here the purchased commodities are thrown into the process of production [C … P], after which the capitalist is left with a series of commodities of greater value than those initially purchased [P … C’]. The creation of additional value is due to the workers who are paid less than the value they create. In our example the capitalist may pay €500 in wages but the workforce produces €1,000 of value, thus netting a surplus of €500. At the end of stage two the capitalist is left with a series of commodities, in this instance cakes, worth €1,500.

In the final stage of the circuit [C’ – M’], the newly created commodities are brought to market and the commodity capital is returned to the capitalist once more in the form of money capital (M’) which incorporates the surplus extracted through the process of production. The capitalist started with €1,000 and ended up with €1,500, yet had the capitalist not foreseen a capacity to turn M into M’ it is only common sense that the circuit would break down, after all what capitalist is keen on spending €1000 to lose a portion of it? Finally, the process is conceived of as a circuit because M’ at the end of the circuit becomes the M for the next circuit. Thus it is better conceived of as a circle rather than a line as seen in the figure below. For a more detailed overview of this process, see Capital Volume 2, Chapter 1.

2.

The Federal Reserve Bank of Saint Louis describes the velocity of money as:

The frequency at which one unit of currency is used to purchase domestically- produced goods and services within a given time period. In other words, it is the number of times one dollar is spent to buy goods and services per unit of time. If the velocity of money is increasing, then more transactions are occurring between individuals in an economy.

The frequency of currency exchange can be used to determine the velocity of a given component of the money supply, providing some insight into whether consumers and businesses are saving or spending their money.

The figure below demonstrates how the velocity of M2 Money Stock has continued to collapse since the 2008 crisis.