As we celebrate the sixty-first anniversary of the Cuban Revolution, a great Irish friend, loyal defender of Cuba, asked me to write for Socialist Voice about the imprint of Fidel Castro and Ernesto Guevara on the most important event of the twentieth century in Latin America—not without first clarifying for me, with the typical frankness and the classic and imperative Irish style: it had to be brief.

A difficult and risky task: to synthesise in brief the role of these two historic figures. Sharing risks with my Irish brothers and sisters, similar to the Cubans in the pleasure of facing dangers, here are my impressions about Fidel Castro Ruz and Ernesto Guevara de la Cerna and their fruitful revolutionary work.

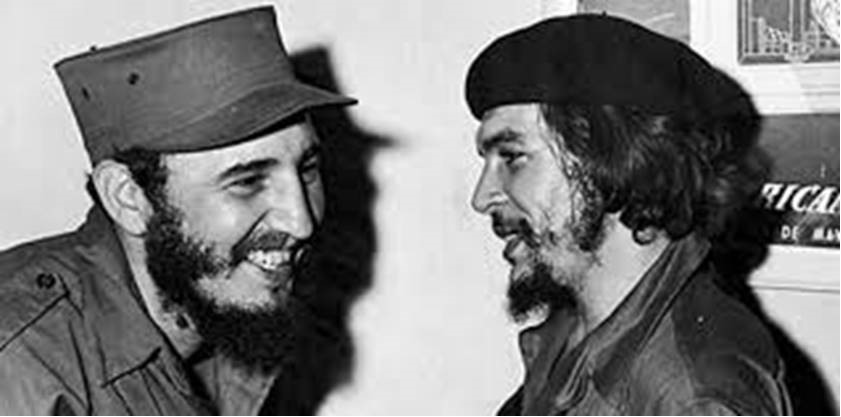

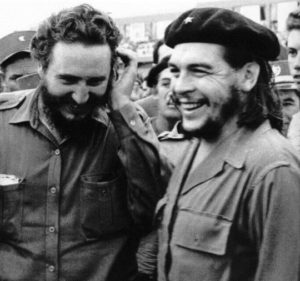

The history of the Cuban Revolution cannot be written without mentioning the names of Fidel Castro and Ernesto Guevara—known all over the world for the name given to him by the Cubans for the interjection used by Argentines in their daily speaking: Che.

They had a mutual admiration. Che said that while imprisoned in Mexico he told Fidel that he was a communist, and that this could jeopardise the plans for the expedition and the start of the revolutionary war in Cuba. Fidel’s answer was categorical: “I will not leave you alone. You are leaving with us.” And so Che, along with Raúl Castro, were the two names that started the list of the eighty-two expeditionaries of the yacht Granma that left Tuxpán, Mexico, on 25 November 1956.

That response and firm attitude of Fidel made Che Guevara admire and completely trust the Cuban leader throughout his revolutionary life.

In an article published by Che, “Cuba: Historical exception or vanguard in the anti-colonial struggle?” he raises with respect to Fidel and his role in the Cuban Revolution:

Let us therefore consider the factors of this alleged exceptionalism. The first, perhaps the most important, the most original, is that telluric force called Fidel Castro Ruz . . . Fidel Castro did more than anyone in Cuba to build the formidable apparatus of the Cuban Revolution out of the blue.

Fidel is undoubtedly one of the most relevant politicians of all time. His revolutionary vision penetrated the most remote places in the world to become an example of self-denial, patriotism, and intransigence against injustice. The truth is that his career as a leader demonstrates a deep and sustained unitary vocation.

The history of Latin America, the Caribbean, Africa, and Asia, the movement of non-aligned countries, the independence and liberation of fraternal peoples, and the defeat of the oppressive apartheid, to the unconditional support for the Bolivarian Revolution, the creation of ALBA, and the unitary basis within the diversity that led to the constitution of the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC), record Fidel Castro’s prestige and moral authority over the past six decades.

Fidel, like Che, was a profound internationalist. His statement “to be internationalist is to pay our own debt to humanity” deeply touched the Cuban people, whose children carried out honourable internationalist missions, both civil and military, in many countries.

Since the initial days of the Cuban Revolution, when it was not known whether he would survive this risky mission, Che had already told Fidel that when the time came he did not wish to be obstructed in his eagerness to fight for a better future for the peoples of Latin America, among whom he had travelled and whose misery increased his thirst for social justice. On these trips he came to the conclusion that the solution to their problems was not the action of a single man but the action of an organised liberation movement on a continental level. Hence the reason for its internationalist action in Bolivia.

After nine years of outstanding service towards the Revolution—and consistent with that agreement he had reached with Fidel—in March 1965 he resigned his positions in the government and in the party, even as a Cuban. “Nothing legal ties me to Cuba any more,” he said in his farewell letter. “Other lands in the world demand the support of my modest efforts.”

Che was not only an excellent soldier, he was also a man of science and ideas. Among the many responsibilities he held in Cuba were minister of industry and president of the National Bank. His views on the Cuban economy and its economic model are well known; he said:

The rationality of the economic model should be in consequence with the social rationality of that model and not the other way around. It is not a question of the quantity and quality of processed material goods but of the way in which they are produced and of the social relations established in that method of production.

The general conception in which the economic model to be followed would be formulated is summarised in the answer given by him to the journalist Jean Daniel published in the French weekly L’Express on 25 July 1963:

Economic socialism without Communist morality does not interest me. We fight against misery, but at the same time we fight against alienation. One of the fundamental objectives of Marxism is to make the individual interest disappear . . . If communism neglects the facts of conscience, it can be a method of division but it ceases to be a revolutionary morality.

In total agreement with Che, Fidel stated:

I have great confidence in socialism and I have very little confidence in capitalism . . . Capitalism stimulates selfishness, corrupts people, does not develop the spirit of solidarity, of fraternity among men, but selfishness, individualism, and therefore I prefer the socialist formula, even within an underdeveloped country . . . Life forced us to use the socialist path for development; then we really have to forget capitalism and follow the socialist path of development, which, in my opinion, is the only way out for the Third World countries . . .

Capitalism is a decadent system in history and will have to be overcome by socialism; although socialism still has many faults, it has deficiencies; but the deficiencies are not in the system, they are in men . . .

Fidel Castro and Che Guevara contributed irreplaceable elements to Marxism and the theory of the struggle for national liberation. Its legacy and action have a marked influence on the struggle for socialism and human improvement. Its thinking, which brings together the best of the traditions of the world revolutionary movement, becomes a source of study and inspiration for peoples in the struggle for national liberation.

In the early 1990s someone announced the end of history and the disappearance of paradigms and even the possibility of finding new ones. The struggles of the peoples in all the continent are the most resounding refutation of that statement, using images of Che and the ideas of Fidel. They are and will be eternal paradigms of peoples in their struggle for a better world.

■ Javier Domínguez, a former combatant of the Cuban internationalist mission to Angola, worked for the Cuban Institute for Friendship with the Peoples (ICAP), generating international solidarity. He visited Ireland twice in the mid-1990s, working with the Cuba Support Group. He lives in Havana.