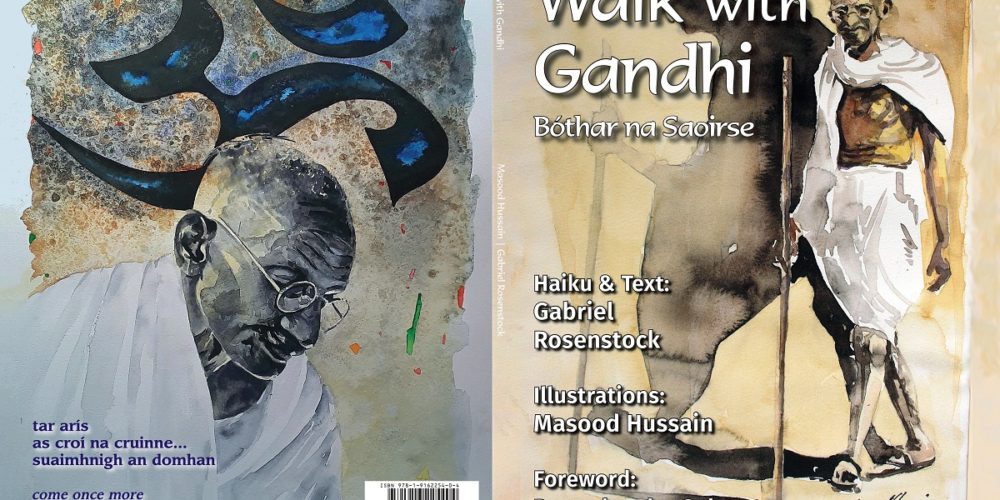

Gabriel Rosenstock, Walk with Gandhi / Bóthar na Saoirse, illustrated by Masood Hussain (Dublin: Gandhi 150 Ireland, 2019, paperback, hardback, and Ebook).

This is a beautiful book to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the birth of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi on 2 October 1869. The book is a collection of haiga—a style of Japanese painting often accompanied by a haiku poem. The artists are the watercolourist Masood Hussain from Kashmir and the Irish poet and haikuist Gabriel Rosenstock.

Hussain’s exquisite watercolours are a reinterpretation of historical photographs taken of Gandhi. Rosenstock’s haiku are in Irish and English. This is significant, as one of the main themes of the book is colonialism and Gandhi’s awareness and opposition to it, including the colonising function of language.

colder than all the prisons

you’ve been thrown into . . .

Downing Street railings

In addition to the amazing interplay of the two art forms, the book is interspersed with fascinating insights into Gandhi’s life and philosophy. These reveal that the book is designed to make Gandhi accessible for the younger generation. They invite readers to consider historical events, forms of protest and the effects of colonialism and relate them to the present.

The information put together for the readers is not designed to turn Gandhi into a saint. It relates aspects that surprise us, for example that “he achieved much for the status of his fellow Indians in South Africa . . . but native Africans—such as Zulus—do not hero-worship Gandhi today. Au contraire! Gandhi took the side of the British in the Zulu uprising of 1906.”

It was in South Africa that Gandhi’s journey began, when he was thrown off a train for sitting in a “whites only” carriage. This awakening was the beginning of his lifelong quest for freedom and justice. Nelson Mandela said about him later, in India: “You gave us Mohandas; we returned him to you as Mahatma.” Many of the tactics Gandhi first used in South Africa he employed again in India.

Back in India, in 1915, Gandhi’s friend, the poet Rabindranath Tagore, gave him the title Mahatma, “great soul,” a name Gandhi never warmed to; it deified him in some way.

Tagore makes several appearances in this book. One of these connects him to the Irish anti-colonial struggle: Patrick Pearse was in correspondence with Tagore, and the latter’s play The Post Office had its world premiere in the Abbey Theatre in 1913.

This book explores many facets of Gandhi’s life. For the younger readers it could well be a first introduction to ideas of colonialism. For example, the following haiku echoes Frantz Fanon’s book The Wretched of the Earth:

are there hats enough

to go round . . .

the wretched of the earth

In the following haiku Rosenstock gently hints at India’s own discrimination against the “Untouchables,” not without a reminder that “many societies have their own forms of class discrimination, snobbishness and exclusiveness, often based on dress, accent, schooling, money, property and other outer distinctive markings.”

a hand

like any other hand . . .

the untouchables

This book is a gem. It is a beautiful book, a wonderfully enriching pleasure in aesthetic appreciation and engaging the mind. It quotes many people on the significance of Gandhi’s philosophy of non-violence, such as Albert Einstein’s: “I believe that Gandhi’s views were the most enlightened of all the political men in our time. We should strive to do things in his spirit: not to use violence in fighting for our cause, but by non-participation in anything you believe is evil.”

To finish with a quotation from Gandhi himself, one that struck a particular chord with me is “Poverty is the worst form of violence.”