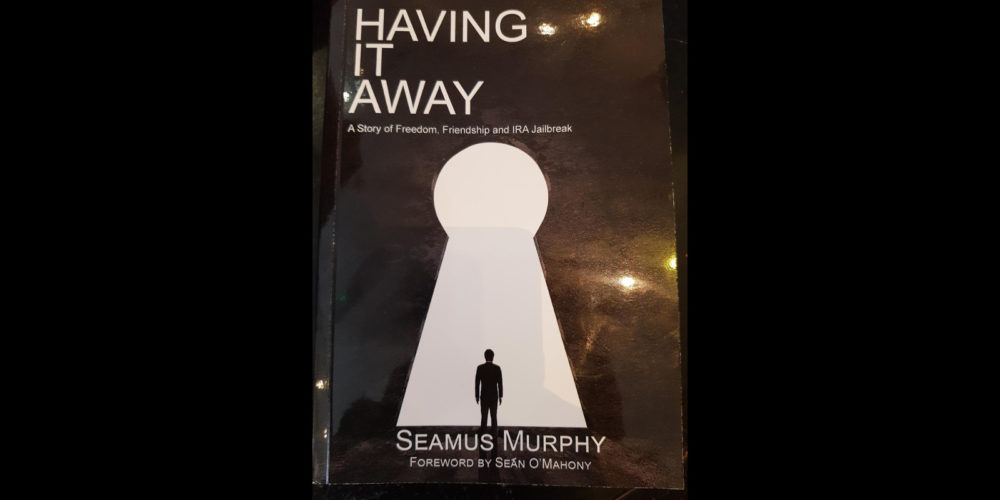

Séamus Murphy, Having It Away: A Story of Freedom, Friendship and IRA Jailbreak (Bray, Co. Wicklow: Castledermot Press, 2019; €10).

“Having it away” was a slang term in the English prisons of the 1950s for making an escape. It is the title of Séamus Murphy’s account of his imprisonment in Wakefield Prison, Yorkshire. He was one of three IRA men caught during a raid on a British army depot near London in August 1955. Aged only twenty, he was given an extraordinarily harsh sentence of life imprisonment.

Despite the title, the escape plays only a small part in this splendid book. Instead we get a well-written and honest look at life inside the British prison system of the 1950s, and much more.

The brutality of the prison warders is evident; but Murphy also describes the people incarcerated, including many unfortunate Irish people, who had been forced to emigrate from Ireland.

A Ukrainian fascist was also a prisoner (though not because he fought on the side of Hitler against the Soviet Union). Reference to fascism in Ukraine reminds one of the dominant role it now plays in that country, thanks to its nurturing by the United States and the European Union. The author does not hesitate to bestow his own scathing judgement on the Nazi collaborator.

Indeed Murphy’s socialist republicanism shines through the whole book as he writes about a host of issues, from the Catholic Church to the Land War and many other historical events. And there are insightful cameos of many different inmates, including Cathal Goulding, the Soviet spy Klaus Fuchs, and the politically mixed group of Cypriot EOKA fighters who found themselves in Wakefield along with the author.

Among the prison population was a sizable number of gay men. Homosexuality was a criminal offence in England at the time. The author relates a tragic story of one unfortunate man who escaped the brutal regime by suicide.

But there is also humour: Séamus’s conversion to vegetarianism is one example. And there was resistance, including the many plans to escape. In the midst of these endeavours, the dark and deadly hand of British military intelligence appears; so too do the ubiquitous divisions inside the republican movement.

Betty Murphy is to be congratulated for ensuring the publication of this volume. The book left me with one real regret: not having got to know “Lifer” Murphy properly when we would meet at the Gralton and later the Greaves Schools.