Towards the end of November the Irish media published reports of comments made by Prof. Christian Kastrop, a former associate of the German minister of finance, Wolfgang Schäuble, one of the architects of the debt crisis. Kastrop now works for the Bertelsmann Foundation, a think tank sponsored by the Bertelsmann Group, one of the principal German transnational corporations.

The “learned” professor suggests that in the euro crisis Ireland was caught in the crossfire between Germany and southern European bail-out countries and was forced to bear “unnecessarily harsh austerity measures.”

We as a people need to keep in mind that we were forced to take ownership of 42 per cent of all banking debt by the European Union, dominated, as it was and is, by German monopoly capital. A significant part of the banking debt imposed was owed to German banks.

A decade of “austerity” has left a trail of hospital waiting-lists, a housing crisis, and cuts in workers’ wages and conditions, a decade in which workers have experienced a growing spread of precarious employment, precarious shelter, precarious health services, and a precarious future for pensioners.

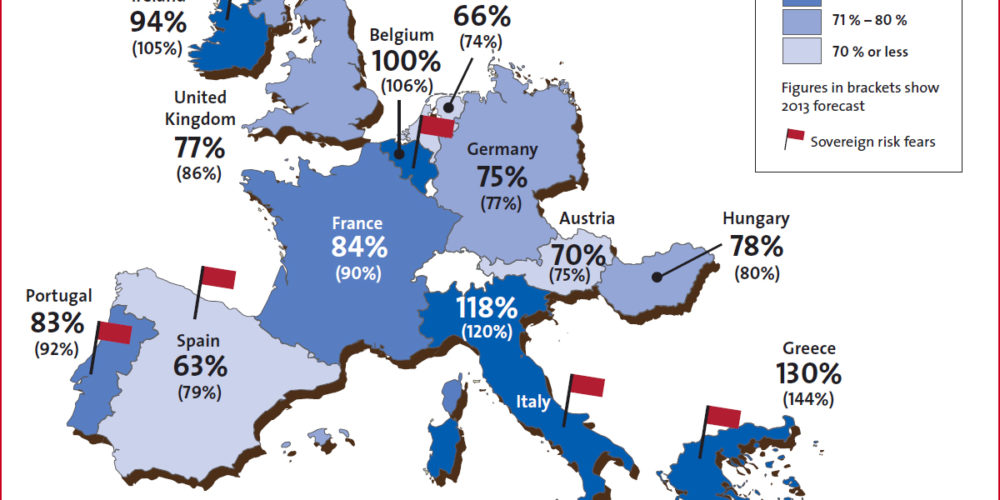

The learned professor put this down in particular to “historical trauma” regarding debt and inflation in German historical experience. While this may have played a small, subjective part in their thinking, what is clear is that German monopoly capitalism would have experienced a huge crisis if Ireland—like Italy, Spain, Portugal, and Greece—had refused to take responsibility for the massive over-borrowing and speculation by financial institutions, both national and global.

“Austerity” was for saving the system, saving finance capital. The crisis presented an opportunity for the ruling class throughout the European Union and beyond to seize the moment and launch an assault on the working class, to take back from workers what they had forced from the elite over many decades. The learned prof., like all such elements within academia, played a necessary role in forming the ideological building-blocks to sustain the system.

Not alone was “austerity” an attack on the living standards of workers and their communities, it was also an ideological attack on the idea of public debt and borrowing. Kastrop played a central part in drafting what are called “fiscal brakes,” adopted since 2016 for the German federal budget and from next year for Germany’s sixteen federal states, which have also been adopted and imposed by the EU.

The German state and ruling class believe in cutting public services, slowing economies first, to maximise the effect of public funds invested subsequently as stimulus. These “fiscal brakes” will prevent current and future German finance ministers from borrowing more than 0.35 per cent of economic output, at the federal level since 2016 and from next year in the provinces. In Germany this has contributed to years of chronic underspending on education and physical and digital infrastructure.

These fiscal rules will be imposed throughout the EU from next year and will have a very negative impact on workers and their families and on public services as more and more of the tax take comes from working people, and taxes on capital are subsequently reduced.

The Irish Fiscal Advisory Council—a Government-appointed think tank of tame individuals—recently issued a report outlining the over-dependence on tax revenue from corporate tax. They make the claim that up to €6 billion, or 60 per cent, of the Government’s corporation tax may be temporary, only for as long as it suits transnational corporations to declare their taxes here in tax-haven Ireland.

Corporation tax rose to a record €10.4 billion last year, more than double the amount collected in 2014. This is caused by what is called the “onshoring of assets,” which is due in some measure to a small global clampdown on transnational tax avoidance and growing global corporate profits. About half last year’s total came from a mere ten companies, such tech giants as Apple, Microsoft, Dell, Google, and Oracle.

The Fiscal Council noted that corporation tax receipts now account for one in every five euros of tax collected by the Government. It also warned that between €2 and €6 billion of the current €10 billion total may be what it calls “excess,” or a temporary aberration in the tax take—what we would term “imperial rent,” whereby the Irish establishment rents a brass plate in the International Financial Services Centre to transnational corporations, where they can wash their profits through the Irish tax system and cream off a few billions of those profits—profits accrued from the savage exploitation of workers around the globe.

These corporations will only continue to declare profits here until another subservient client state offers them a better deal. The increased Government spending is financed in part by these corporation taxes and is not a true reflection or based on the real strength of economic activity here, and is thereby not sustainable in the long term. This is where the EU fiscal rules on government borrowing will have a significant impact when these sources of tax revenue dry up or are reduced.

Once again workers will face further and ever deeper attacks on their wages and conditions. Services such as health and education will come under further attack. Neither will the housing crisis be solved with the Government’s current strategy. We will see a further tightening of the power and control of finance capital.

Workers will always be made to pay the price for the recurring crisis. What is needed is a radical break with this failing and crisis-ridden economic system.

Those who continue to argue for the system, and those who argue that membership of the EU is the only way forward but simply needs progressive reforming, need to explain how this is to be done.