The greatest of the sixteenth-century Dutch realists is without doubt Pieter Bruegel the Elder. Born about 1525, Bruegel died 450 years ago, on 5 September 1569.

His lifetime coincides with the struggle of the Netherlands against Spanish domination. At that time it included Belgium, Luxembourg and part of northern France as well as the territory of the present-day Netherlands. It belonged to the Holy Roman Empire and was dominated by the Spanish branch of the Habsburgs. Bruegel’s lifetime included a stepping up of the Inquisition, the persecution of Protestants, and Calvinist iconoclasm.

Bruegel was the first of a large family of painters. He became known as “Peasant Bruegel” because of one of the main features of his work, the centrality of the Dutch peasantry. However, his art reflects Dutch reality in many more ways. Not only did it draw inspiration from popular expressions and proverbs, and put the people of the Netherlands at its centre, his paintings for that very reason contain many hidden attacks on Spanish domination. In this way such works as The Procession to Calvary, Census at Bethlehem, The Massacre of the Innocent, and many others, sometimes cloaked in religious guise, helped to prepare the Dutch Revolution by putting on canvas the realities of the ordinary people and thereby supporting the Dutch quest for independence.

In The Procession to Calvary, Jesus is wearing the same blue clothes as the peasants who are coming to his aid, both women and men. The red-coated mercenaries, all on horseback, are clearly depicted as their common enemy.

The domination of the Dutch peasantry by the Spanish oppressor is also very apparent in the two paintings Census at Bethlehem and The Massacre of the Innocent. Both are set in freezing landscapes. Both carry a political comment about the Dutch or Flemish under this Habsburg branch of the Holy Roman Empire.

In Census at Bethlehem the people clearly suffer from the financial and military yoke of the foreign power. They queue to register and to pay taxes to the empire. Tellingly, the tax-collectors sit next to the Habsburg coat of arms (a black eagle on a golden shield), painted on the wall beside the window. Mary and Joseph are shown heading towards the tax-collectors. They too are depicted as Dutch people in subjugation.

Bruegel’s sequence on the seasons has its roots in the Book of Hours, but they have come a long way. These paintings mastered the seasonal atmospheric values of nature for the first time and organically integrate in the landscape the ordinary working people.

In his winter landscape Hunters in the Snow the hunters and their dogs return from their work. They are bent over with tiredness on their way home to the village. In this painting Bruegel’s training as a miniature artist is spectacularly clear in the amount of life going on in the distance. The viewer sees the expansive landscape through the hunters’ eyes, following their footsteps across the snow-covered ridge. Villagers skate; a woman crosses a bridge carrying brushwood; even a chimney fire can be detected in the village’s furthest cottage, with villagers working hard to extinguish it. Icy cold blows towards the observer, and one senses the shelter that the huts offer their inhabitants.

Bruegel celebrated the deep-seated traditions of Dutch culture, showing the threat by the Catholic King Philip II of Spain. Most famous of all are, of course, Bruegel’s depictions of peasant life, as for example in The Wedding Dance. This very “this-worldly” picture would have been frowned upon by the Church, which disapproved of dancing and any obvious sensuality or joy in life.

At the centre of this picture we see the joined hands of bride and groom, who are dancing in the open air. The bride is the only woman without a white scarf and the working women’s apron; her red hair is loose, and she is wearing a black dress. (White dresses became fashionable only in the nineteenth century.) The entire village is invited, and it is a joyous community occasion.

The dynamic movement within the picture is stunning, expressing the people’s enormous energy, and one can easily imagine the bagpipe music. Aside from the dancing there is sexual freedom among the villagers too. The bagpipe itself is a sexual symbol, apart from being a folk music instrument. The unrestrained enjoyment of life, the energy, the dancing, music and sexual freedom are all a clear statement of resistance to the political and religious control of the Dutch people.

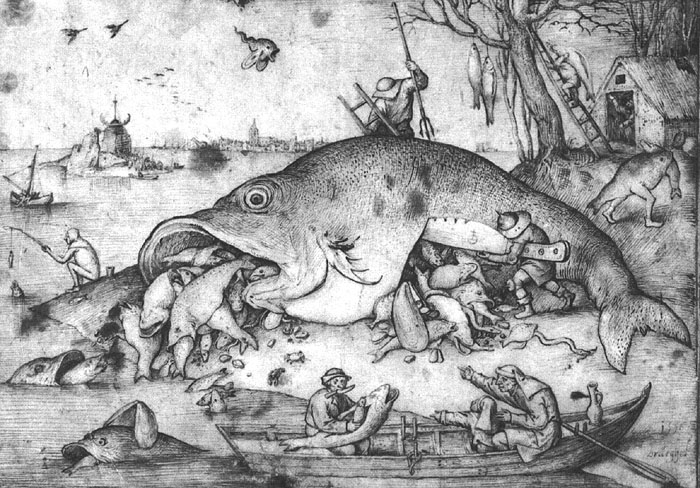

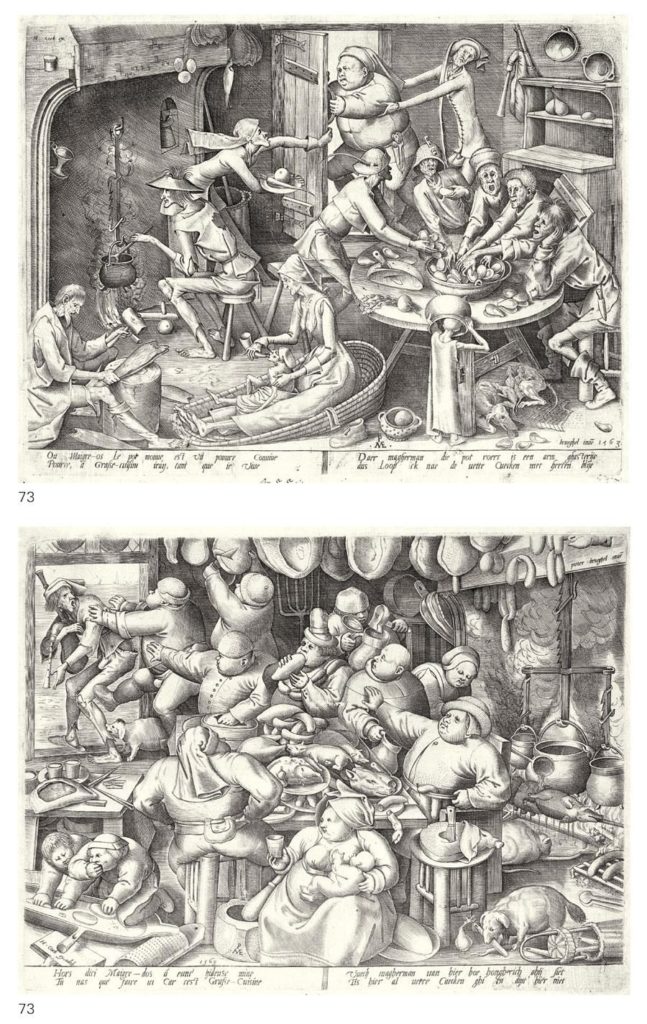

Bruegel also produced more directly socially critical allegorical works, such as Big Fish Eats Small Fish and the not so allegorical pair The Poor Kitchen and The Rich Kitchen, enjoyable, recognisable, and true to this day.

Bruegel captured his time from the point of view of the subjugated people in a remarkable and realistic, humane way. His art represents the early stages, the progressive, indeed revolutionary element of bourgeois realism.

For this reason viewers today can easily understand and identify with Bruegel’s partisanship with the ordinary, exploited and oppressed folk and their rebellion against their condition.