There are few people more famous in the political song movement than Pete Seeger. Along with his contemporaries Paul Robeson and Woody Guthrie, Seeger represented the might of song in highlighting the common cause, strengthening courage, and inspiring resistance. Song was their weapon in this struggle for a fair, equal and peaceful society.

Pete grew up in a musical family. His father, Charles, was a musicologist and lecturer who lost his job when he opposed America’s involvement in the First World War. His mother, Constance, was a violinist, and also held socialist and pacifist political views.

His parents divorced when Pete was a child. Charles remarried and joined the Composers’ Collective, who performed their songs for strikers and the unemployed. The family travelled the country, playing music and attending folk festivals on many occasions. It was here that Pete encountered the banjo and made it his instrument.

In 1936, at the age of seventeen, Pete Seeger joined the Young Communist League, and in 1942 he became a member of the Communist Party of the USA, which he left in 1949.

In 1938 he enrolled in a sociology course at Harvard University, in the hope of becoming a journalist, but ultimately he did not not finish it. He went to New York, where he met Woody Guthrie, Alan Lomax, Lead Belly, and others, deeply involving him with traditional American music. They jointly founded the Almanac Singers in December 1940. With their pro-union songs and singing against racism and war, the band propelled Seeger into an active political folk-song scene. They performed for strikers with such songs as “Talking Union” and others about the struggles for the unionising of industrial workers.

In June 1942, following Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union, Seeger enlisted in the US army in order to fight fascism. He worked on aeroplane engines and later transferred to Saipan in the Western Pacific to entertain troops. Military intelligence considered him unfit for “a position of trust or responsibility” because of his “Communistic sympathies, unsatisfactory relations with landlords and his numerous Communist and otherwise undesirable friends,” and described the Almanac Singers as “spreading communist and anti-fascist propaganda through songs and recordings.”

Seeger was a fervent supporter of Republican Spain against Franco, and in 1943 he recorded several Spanish Civil War songs with like-minded musicians. The album was entitled Songs of the Lincoln Battalion.

After the war Seeger established People’s Songs Incorporated. “I hope to have hundreds, thousands, tens of thousands of union choruses,” he said. “Just as every church has a choir, why not every union?”

Soon the PSI had two thousand members, and it was growing fast. An FBI file was opened on the organisation.

In November 1948 Seeger jointly founded the folk group called the Weavers. The group took its name from a German drama about the Silesian weavers’ uprising by Gerhart Hauptmann, Die Weber, which contains the lines “I’ll stand it no more, come what may.” The group recorded “Good Night, Irene,” a song written by Seeger’s friend Lead Belly. The threat of censorship dictated that the chorus be changed from “I’ll get you in my dreams” to “I’ll see you in my dreams.” The record topped the charts in 1950.

The band also popularised Guthrie’s song “This Land Is Your Land” and other left-wing songs, such as “If I Had a Hammer.”

From about 1940 Seeger’s support for civil rights and workers’ rights, racial equality, international understanding and peace had made him a suspicious character in the eyes of the state. In 1955, during the McCarthy witch-hunt era, Seeger and his fellow Almanac singer Lee Hays were identified as Communist Party members and were summoned to testify before the House Committee on Un-American Activities. Seeger refused to answer, claiming the protection of the First Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, which guarantees freedom of speech—the first person to do so after the conviction of the Hollywood Ten in 1950. The House of Representatives found Seeger guilty of contempt, but in 1961 it had to overturn this conviction on technical grounds.

However, anti-communism was rampant since the beginning of the McCarthy era, and the band suffered from a total boycott by the establishment. Right-wing groups sabotaged their concerts, ultimately leading to the group’s dissolution in 1952. For seventeen years the American media ostracised Seeger.

He performed at schools and colleges and for minor trade unions. This meant smaller audiences, but nevertheless Seeger reached a lot of people, some of whom later found jobs in the trade union movement, were involved with festivals, with Hollywood, on the radio, or in the theatre. Famous bands popularised songs written by Seeger from this time, including “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?”—a song that came to him when reading Sholokhov’s novel And Quiet Flows the Don.

In 1957 Pete met another victim of FBI surveillance and intimidation, Martin Luther King, at the Highlander Folk School in Tennessee. Here began what would become the anthem of the civil rights movement, “We Shall Overcome,” changing slightly the hymn “I Will Overcome.” In 1963 Seeger sang it on the fifty-mile walk from Selma to Montgomery, along with a thousand other marchers.

Seeger was joint founder of the music magazine Sing Out! and a senior figure in the 1960s urban folk revival. The movement, which Seeger called “Woody’s Children,” after Guthrie, adapted traditional songs for political purposes. The Industrial Workers of the World (Wobblies) had pioneered this in their I.W.W. Songs: To Fan the Flames of Discontent, popularly known as The Little Red Songbook. This was originally compiled by the legendary union organiser Joe Hill, and was a favourite of Guthrie’s.

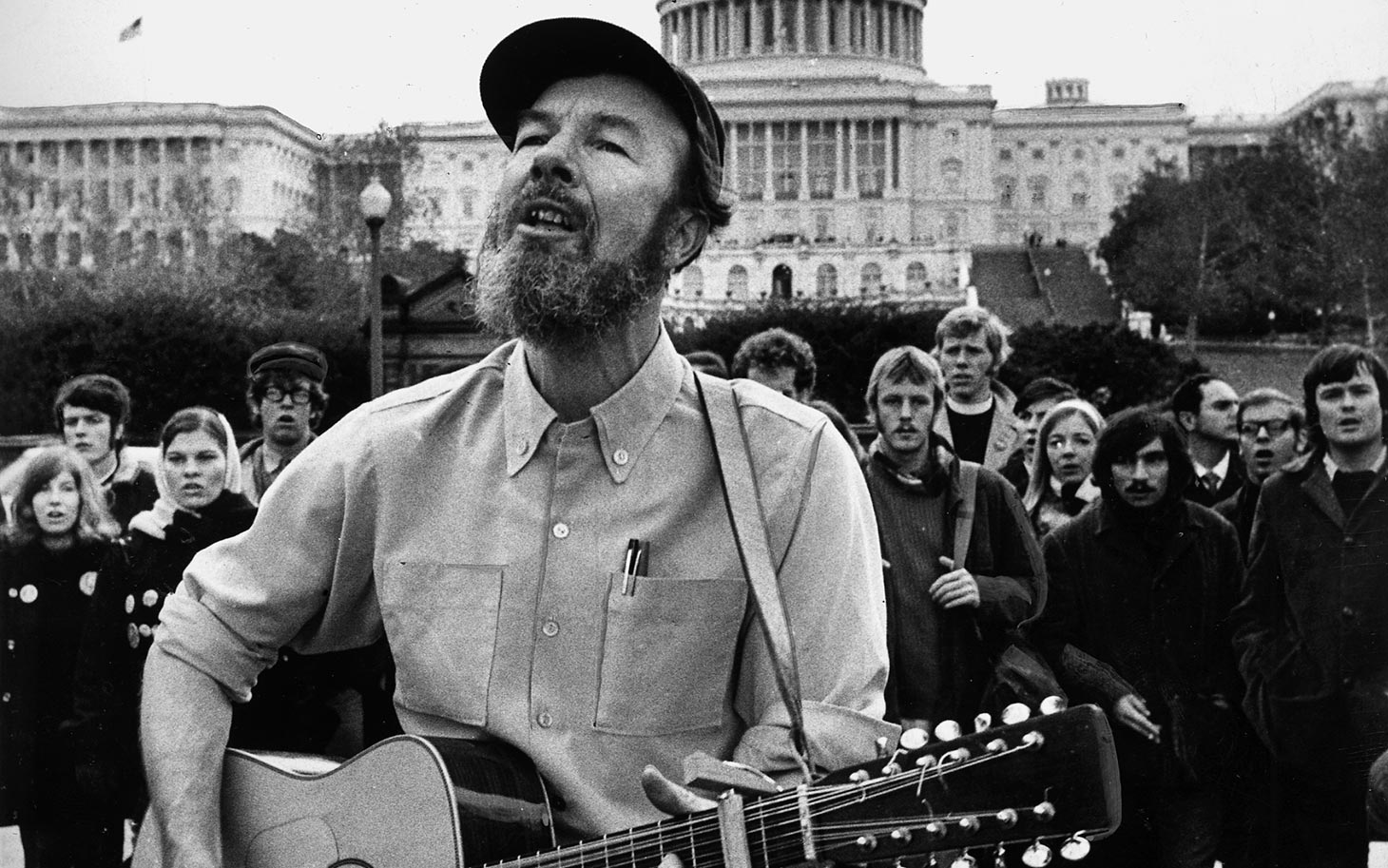

Like King, Seeger was a vocal critic of the US war in Viet Nam, writing popular anti-war songs such as “Waist-Deep in the Big Muddy” and “If You Love Your Uncle Sam (Bring ’Em Home).” On 15 November 1969 the Viet Nam Moratorium March on Washington took place. Seeger led half a million protesters in singing John Lennon’s peace song “Give Peace a Chance,” calling to Richard Nixon at the White House, “Are you listening?”

Pete Seeger and his wife, Toshi Ohta, lived in a log cabin overlooking the Hudson River. Disturbed by the river’s pollution, they jointly started the Great Hudson River Revival, which became known as the Clearwater Festival. In this way they were instrumental in rallying public support for cleaning the Hudson River and surrounding wetlands. The festival now attracts more than 15,000 people each summer.

Seeger remained politically active into his nineties. In 2012 he performed with Harry Belafonte, Jackson Browne and others for Leonard Peltier of the American Indian Movement, who has been in prison for over forty years.

Pete Seeger died on 27 January 2014, aged ninety-four. He played an active role in all the important struggles of the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries—for peace, for the environment, for civil and workers’ rights. His memory is inscribed indelibly in the minds of all those who are part of the same movements when they sing, “We shall overcome.”