The New Year and the annual (temporary) surge in gym membership, attendance at diet groups and body-shaming begins anew.

In the coming days and weeks women (and, increasingly, men) will be cajoled or bullied by television programmes, magazine covers, newspaper articles and advertisers to lose a dress or trouser size, trim their waist of the Christmas fat, and begin working towards a “new and better you”—all this building to a deafening climax in the summer months as these same people are placed under orders to get “beach-body ready.”

More recently, this shaming has taken the lead in a pseudo-health outlook and articles dripping with faux-concern about getting people to eat better and exercise more; the aim of a more trimmed figure has remained the same, but it’s a clever way of reinforcing old stereotypes regarding the moral fibre of overweight people: they must be gluttonous and lazy and entirely responsible personally for their own failings.

This shaming has a strong classist element. Research published in 2017 by the International Journal of Public Health shows that it is the working class in developed countries who are at the highest risk of both malnutrition and obesity. The Central Statistics Office confirms the pattern here, with Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown one of the healthiest parts of the country and the city of Dublin the unhealthiest.

More and more people in Ireland are now living in a “food desert”—an area where poverty, poor transport and the pushing out of the once ubiquitous local greengrocer, butcher and baker mean that access to affordable fresh and nutritious food, such as vegetables, can be an impossibility. These are often deprived areas, which are also “food swamps,” dominated by cheap fast-food outlets.

Not surprisingly, there is a strong overlap between food deserts, food swamps, and obesity rates. Research published in 2017 in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health showed that food swamps were more prevalent in working-class areas, and a greater predictor of obesity than food deserts. This easy access to unhealthy food, along with the ever-increasing demands placed on workers’ time, makes the €1 burger a more sensible option than an expensive and time-consuming trip to the nearest supermarket, followed by cooking, for a healthier alternative.

The increasing financial pressure of ever-increasing rents or mortgage repayments means that the weekly grocery budget can be one of the first things to suffer. Calorie-heavy and dense carbohydrates keep a family fuller longer, last longer, and are easier to store than healthier produce, such as vegetables, which have limited shelf life, even with refrigeration.

Convenience food can also be one of the pleasures left to workers and their children when they are barely making the rent and bills. Let them have a takeaway if they can’t have new shoes or a warm house.

Obesity, at its most scaremongered, is reported to lead to an increased risk of heart disease, cancer and diabetes if a clinically obese person has an existing condition such as high blood pressure, blood sugar, or cholesterol. Anorexia and bulimia, which are also on the rise globally (by 7 per cent each year since the 1990s), are recognised as having the highest fatality rate of any psychiatric disorder, and are considered a life-threatening diagnosis.

The annual medical costs of malnutrition in Ireland are estimated at more than €1.4 billion—more than the estimated costs of obesity; and in both these cases there are few news services highlighting either fact. That is not to say that obesity isn’t a public health issue but that the concern displayed is only because of how it is useful in the pursuit of profit. Obesity is the bigger cash cow.

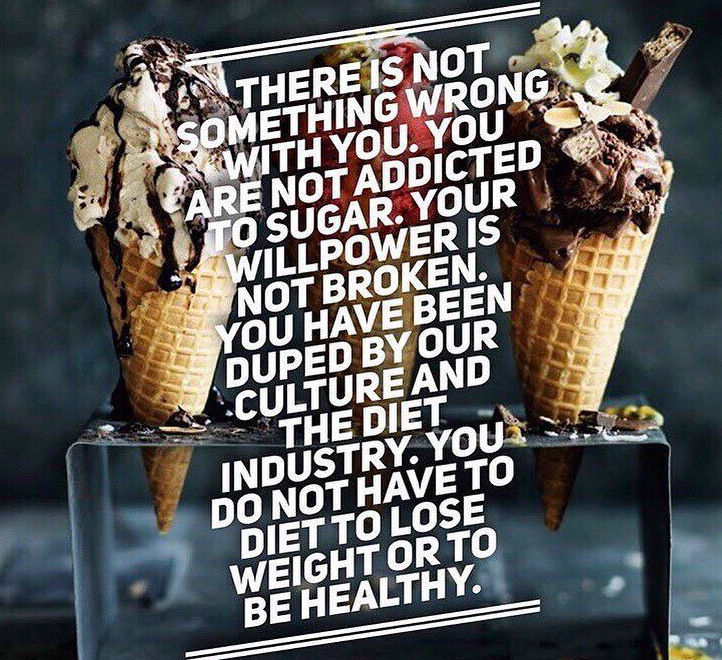

Obesity’s most recommended treatment is shown to actually worsen the problem. A study published in the International Journal of Obesity in 2012 assessed dieting habits in more than two thousand sets of twins. It found that the twin who dieted was two to three times more likely to become overweight than their non-dieting sibling. This is the result of diets tricking the body in a variety of ways, including inducing a starvation response to cull fat.

These have a lasting impact on the metabolism of the body and become harder to correct the more often they are induced. Diet culture is actually contributing to the obesity epidemic it purports to aid in halting.

Dieting is a cynical, multi-million industry, and there are thousands of options to choose from. It sells almost everything that sex is supposed to do, each alternative promising to get the weight off, for a while anyway. But not even a public body like the HSE, in its National Obesity Action Plan, offers a solution to the social factors that cause obesity. SlimFast sums it up best, its slogan “Works for me!” delivered with a backward glancing shrug implying that it’s not their fault and they don’t care if it doesn’t.

Capitalism and imperialism are at the root of the cause, the spread and the ineffective treatment of obesity. Once a rich man’s disease, obesity is now rampant in the developed and developing world. Anywhere that western norms are introduced and capitalism tightens its grips is a place where not only are workers exploited but even the food marketed and pushed will make them ill.

Compared with public health campaigns, such as those for giving up smoking, obesity is treated as an individual weakness or illness. The banning of advertising certain foods to children, as well as the obligation on food companies to make the nutritional content of food readily available, is a start; but the only real way to combat obesity as a genuine public health issue is not to use shame or to rely on a sugar tax but to ask why are working-class people denied access to fresh, healthy food, why is cooking a luxury for those few who are time-rich or financially rich (or both), and where are the school or community cooking courses and community gardens in the areas hardest hit by obesity.

A study published in the British Medical Journal in 2017 shows that socio-economic disadvantage is linked to obesity over generations, which means the solutions have to be intergenerational as well.

Henry Kissinger wasn’t wrong when he said, “If you control the food supply, you control the people.” We just need to take it back.