Global debt is now becoming a major factor in the instability of the system of capitalism. Figures show that in the second quarter of 2018 global debt reached a new record, rising to $260,000 billion.

Of this total, 61 per cent—$160 trillion—is private debt of the non-financial sector, while 23 per cent is government debt.

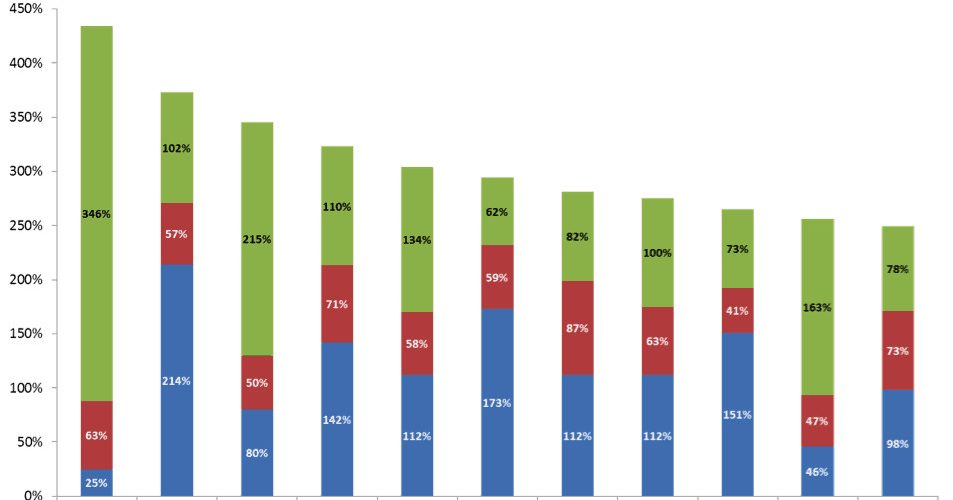

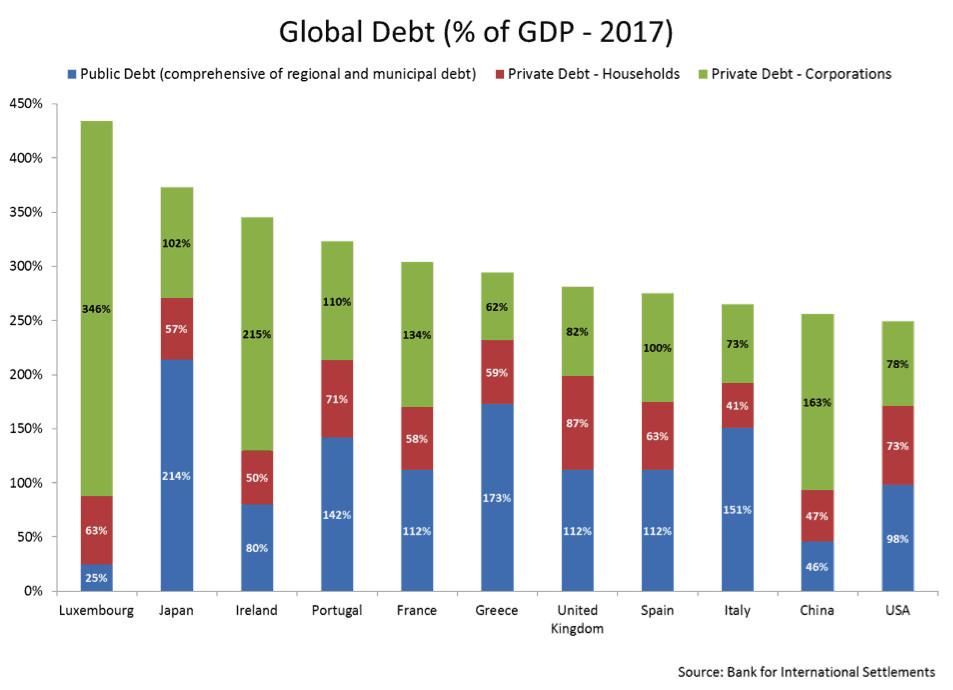

When attempting to assess the debt we need to take into account the ratio of the debt to GDP; this has passed the 320 per cent threshold for the first time (see chart).

The United States alone is responsible for 30 per cent of the outstanding public debt. Trump’s policies in the last two years have accelerated the growth in US government debt. The US Treasury is followed by the Japanese and Chinese debt agencies and the biggest euro-zone economies.

By using GDP as the measure, the positions are reversed: Luxembourg ends up in first place, with a total debt equal to 434 per cent of GDP, composed almost entirely of corporate debt, while Japan’s debt is about 373 per cent; the largest component of this is public debt, standing at 216 per cent. 90 per cent of the debt is in the hands of the central bank, pension funds and domestic banks. France, Spain and the British state are in the top eight for public and private debt.

In the euro-zone countries, states are unable to manage monetary policy independently, as the euro is one of the main mechanisms of control and for imposing fiscal policies on member-states. All public debt of the member-states is de facto subject to foreign law. An average of more than 70 per cent of this debt is held by foreign investors, institutions, and individuals, more reactive in negotiating on secondary markets and in feeding panic selling.

Another factor that needs to be considered is what establishment economists call “implicit debt,” which means that it does not take into account the present value of financial commitments made by governments regarding pensions and health services.

These future debts do not appear in the national accounts and are not projected into future expenditure. If we take these hidden charges into account, possible future US debt could be more than $100 trillion. Spain, Luxembourg and Ireland could see their liabilities rise more than tenfold, over 1,000 per cent of GDP in the case of the Irish state.

These are some of the hard facts behind the push by the state and employers’ organisations for people to have their own private pension schemes and private health insurance, with more and more public money and workers’ wages funnelled into private pension and health schemes, allowing the state to undermine and reduce the public pension.

At the global level, corporate debt is the variable that the markets fear most. A heavily indebted private sector is vulnerable to increasing interest rates.

The inherent instability of debt suggests that the next slowdown in growth could develop into an unusually strong freeze of corporate investments.