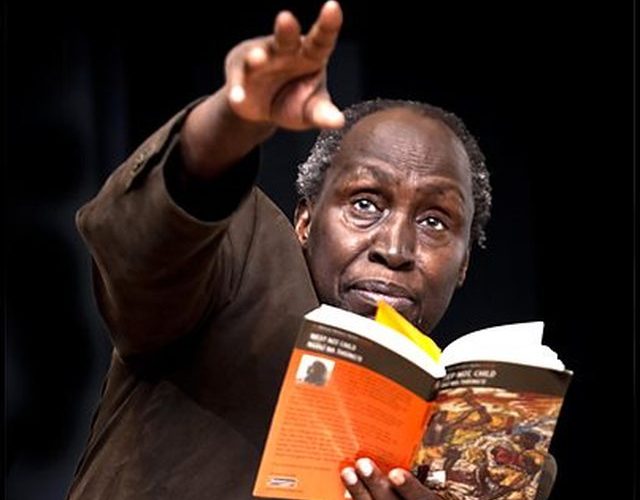

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o turned eighty this year. He has written prolifically. Arguably his most famous (non-fiction) book is Decolonising the Mind, about the constructive role that language plays in national culture, history, and identity.

The reclaiming of African languages as keepers of memory, of African history, became central to Ngũgĩ’s post-colonial struggle.

Ngũgĩ’s epic comic novel Wizard of the Crow (2006), set in the fictitious “Free Republic” of Aburĩria, scathingly describes the corruption, brutality and self-negation of neo-colonial African dictatorship. It outlines the experience of the African continent in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, the slavery of its peoples, the colonial legacy as feeding into the neo-colonial present:

“The Ruler’s rise to power had something to do with his alliance with the colonial state and the white forces behind it . . . His friends in the West needed him to assume the mantle of the leader of Africa and the Third World, for Aburĩria was of strategic importance to the West’s containment of Soviet global domination. The Ruler accused the Socialist Party of forming one link in the chain of the Soviet ambitions. Aburĩria did not fight Western colonialism in order to end up under Eastern Communist colonialism, he declaimed . . . It is said that in only a month he mowed down a million Aburĩrian Communists, rendering the Ruler the African leader most respected by the West . . .”

The leader of the underground resistance is a woman, Nyawĩra, who emphasises a class understanding of society and the need, and possibility, for change. This courageous person finds a partner in Kamĩtĩ, whose opposition to the status quo grows over time as he gets to know and love her. Kamĩtĩ brings to the relationship a tremendous amount of humour, a willingness to hide, heal and mock by impersonating a witch doctor, as well as knowledge of the medicinal properties of African plants. Together they forge the main positive and hope-giving force in the novel.

They are supported by other brave people in the community, including some who grow into this role, some who change sides, and also those who do not betray. The most heroic among those resisting the many manifestations of the regime are women; in fact a women’s court to punish perpetrators of domestic violence is established as part of the Movement for the Voice of the People.

Nyawĩra puts this in Marxist terms: “Those who want to fight for the people in the nation and in the world must struggle for the unity and rights of the working class in their own country; fight against all discriminations based on race, ethnicity, colour, and belief systems; they must struggle against all gender-based inequalities and therefore fight for the rights of women in the home, the family, the nation, and the world . . .”

Throughout this satirical novel the West’s involvement with the corrupt regimes in Africa is highlighted, here in particular with the Global Bank, from which they hope to secure an enormous loan, which in turn will lead to unparalleled austerity. However, the country’s political instability ultimately prevents this. When the country’s autocracy begins to crumble, the West plans a military coup.

Yet Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o rejects the Western journalists’ favourite image of Africa. “They believed that a news story from Africa without pictures of people dying from wretched poverty, famine, or ethnic warfare could not possibly be interesting to their audience back home.” He underlines the humanity of the people. Nyawĩra and Kamĩtĩ’s ability to laugh together at the absurdity of the regime is in itself a sign of their strength.

By rejecting the generalised Western media African stereotype, Ngũgĩ enables the reader to draw parallels with other dictatorships around the world, mentioning those of Marcos, Pinochet and apartheid South Africa at the very end of the book.

One of the most memorable moments in the novel is when one of the characters on the government side becomes afflicted by a psychological condition that makes him want to become white. Kamĩtĩ, as Wizard of the Cow, manages to “cure” him, as he renounces his name and language, in an ironic self-imposed replaying of the fate of the slaves.

Although the government men are corrupt, superstitious, and paranoid, as well as willing to kill indiscriminately for personal gain, they are not beyond grasping where all this will ultimately lead to. “The Global Bank and the Global Ministry of Finance are clearly looking to privatise countries, nations, and states. They argue that the modern world was created by private capital . . . What private capital did then it can do again: own and reshape the Third World in the image of the West . . . The world will become one corporate globe divided into the incorporating and the incorporated. We should volunteer Aburĩria to be the first to be wholly managed by private capital, to become the first voluntary corporate colony, a corporony, the first of the new global order.”

What is distilled in these extracts is written into the fabric of the novel, from where it inscribes itself indelibly in the reader’s imagination and becomes much more. The text is enriched with African fable-telling and humour.

And one thing is made perfectly clear: there is no magic. It is a hilarious, exciting and brilliant read; it is a masterpiece.