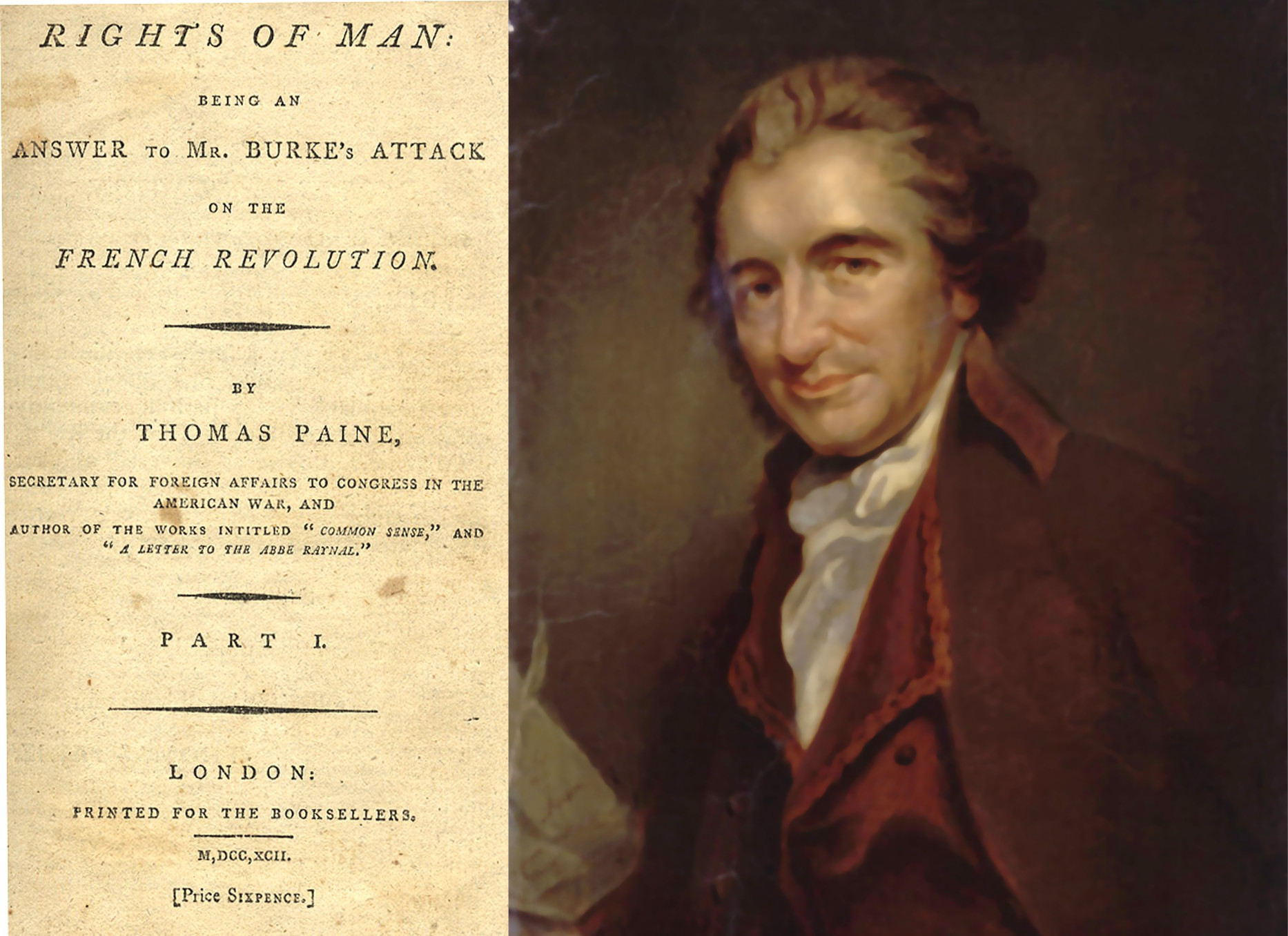

Thomas Paine’s famous work Rights of Man was published in 1791. It was written as a reply to Reflections on the Revolution in France by the Anglo-Irish politician Edmund Burke.

Burke’s book was an attack on the principles of the French Revolution, written by a representative of the ruling class as a warning to prevent the spread of the revolution’s principles to Britain. While Burke uses the language of the ruling class, Paine, who became a stay-maker (corset-maker) at the age of thirteen, writes with the passion and self-conviction of the masses.

Paine challenges Burke on the “right” of any group of men to rule over the people. For him, the people were themselves the sovereign, and not any unelected monarchy. He upholds the right, and duty, of a responsible citizenry to rid itself of this form of tyranny.

While much of the anger of the French third estate (the majority of the people) centred on King Louis XVI, Paine writes that the faults of the system lay not with personalities as such but with the system itself. “It was not against Louis XVI, but against the despotic principles of government, that the nation revolted . . . In the instance of France we see a revolution generated in the rational contemplation of the rights of man, and distinguished from the beginning between persons and principles.”

The Declaration of the Rights of Man, the most important document of the French Revolution, stated that in a republican government all men are born equal, and that the control of state power rests with the people of the nation alone. The European Union seems to have declared this principle to be outdated; indeed the struggle for a sovereign nation-state is still the main political struggle today for democrats.

While in Paine’s time it was a struggle against the forces of aristocracy centred in Britain and elsewhere, now it is a struggle against the forces of finance capital, based in the United States, the European Union, and other imperialist centres.

In part 2 of the book Paine puts forward his own alternative to the ills of the status quo. He creates a fully costed budget for such things as education and health, employment, pensions for the elderly, abolition of the poor-rates, and grants for newly married couples and and for new-born children. These measures would go together with decreasing military spending, made possible by the peaceful interactions between nations that have moved beyond the old order. They would be paid for by the introduction of a progressive tax.

These modest measures would form the backbone of what we now call the welfare state, which became standard in western Europe after 1945. The fact that these measures in the western capitalist states took so long after Paine first wrote about them shows just how late social democracy came to the show. The socialist system then existing in the Soviet Union and eastern Europe had already taken these demands further, being enshrined in the Constitution of the USSR in 1936, while the emergence of neo-liberalism in the 1970s showed these reforms under capitalism to be merely a temporary compromise with the people, with even these basic rights now under attack.

The debate between Paine and Burke represented the first division of politics into left and right wing. The left wing were those who supported the revolution and its belief in the rights of man; the right wing believed in the preservation of the aristocracy.

In Ireland, Paine’s book was a best-seller, and it was a major influence on Theobald Wolfe Tone and the United Irishmen. Tone himself captured the fervour that accompanied the great controversy between Burke and Paine, unmatched until the October Revolution in 1917. He wrote:

“This controversy, and the gigantic event which gave rise to it, changed in an instant the politics of Ireland. Two years before, the nation was in lethargy . . . But the rapid succession of events, and, above all, the explosion which had taken place in France and blown into the elements a despotism rooted for fourteen centuries, had thoroughly aroused all Europe, and the eyes of every man, in every quarter, were turned anxiously on the French National Assembly. In England Burke had the triumph completely to decide the public . . .

“But matters were very different in Ireland, an oppressed, insulted, and plundered nation . . . In a little time the French revolution became the test of every man’s political creed, and the nation was fairly divided into two great parties, the Aristocrats and the Democrats (epithets borrowed from France), who have ever since been measuring each other’s strength, and carrying on a kind of smothered war, which the course of events, it is highly probable, may soon call into energy and action.”