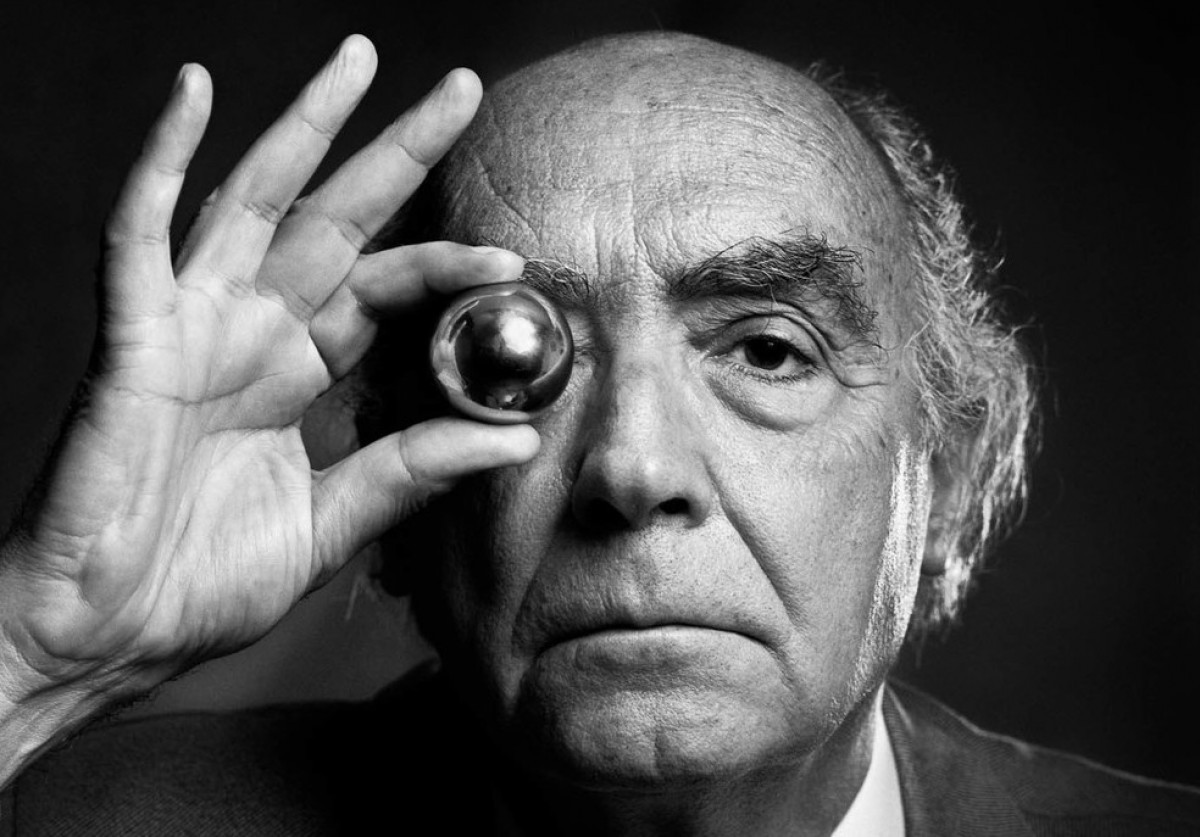

Twenty years ago, on 8 October 1998, the communist writer José Saramago became the first Portuguese author to receive the Nobel Prize for Literature.

The first fifty years of Saramago’s life were defined by the fascist dictatorship that ruled Portugal from 1926 to 1974 and his active resistance against it.

Born the son of landless peasant labourers in a village north-east of Lisbon, Saramago grew up in poverty. He trained and worked as a mechanic, civil servant, metalworker, production manager at a publishing house, and managing editor of a newspaper. He joined the Communist Party in 1969 and remained a lifelong member. He wrote for and helped edit the Communist Party paper for a time, and stood as a Communist Party candidate in the 1989 local elections.

The “Carnation Revolution” of 1974, which put an end to the fascist regime, was much more than the transition from dictatorship to bourgeois parliamentary democracy. The first government to take power was largely communist. Monopolies were nationalised, the large landowners in the Alentejo were expropriated and the land given to the agricultural workers, workers’ control was granted by law, and the colonies were given independence. Although these socio-economic achievements could not be preserved, it set an example that still applies today: another world is possible. This vision of an alternative to capitalism, and human resilience, is an important theme in Saramago’s work.

The communist-led government was replaced in 1975 by a Socialist Party one, and Saramago lost his job as newspaper editor. He then devoted himself exclusively to writing. However, he became increasingly pessimistic about Portugal’s political course. When the government under Aníbal Silva refused to endorse Saramago’s book The Gospel According to Jesus Christ (1991) for the European Prize for Literature, stating that it was too anti-religious to be supported by Portugal, Saramago left Portugal and lived in Lanzarote in the Canary Islands until his death in 2010.

This was no withdrawal from politics. He continued to publicly lampoon capitalism’s hypocrisy, criticising the EU and the International Monetary Fund, defending the Palestinians against Israeli policies, and founding the European Writers’ Parliament along with the Turkish writer Orhan Pamuk; but his main contribution lies in his writings.

Raised from the Ground (1980) is a novel about working people’s life under a dictatorial regime, who take over and occupy land. Blindness (1995) depicts an entire population going blind and how people individually cope and attempt to survive shocking events. Seeing (2004) explores a post-blindness election, in which the people cast their ballot papers, returning them blank. Each novel is different, yet they repeatedly deal with living in the extreme and inhuman conditions of class society and what hope we have.

However, on this anniversary we should leave it to Saramago himself to speak about his writing. We do so by publishing here in full his acceptance speech for the Nobel Prize for Literature, which he won in 1998, at the age of seventy-six. The speech is in itself part of the body of his literary achievement.

***

How characters became the masters and the author their apprentice

. . . Then came the men and women of Alentejo, that same brotherhood of the condemned of the earth where belonged my grandfather Jerónimo and my grandmother Josefa, primitive peasants obliged to hire out the strength of their arms for a wage and working conditions that deserved only to be called infamous, getting for less than nothing a life which the cultivated and civilised beings we are proud to be are pleased to call—depending on the occasion—precious, sacred or sublime. Common people I knew, deceived by a Church both accomplice and beneficiary of the power of the State and of the landlords, people permanently watched by the police, people so many times innocent victims of the arbitrariness of a false justice. Three generations of a peasant family, the Badweathers, from the beginning of the century to the April Revolution of 1974 which toppled dictatorship, move through this novel, called Risen from the Ground, and it was with such men and women risen from the ground, real people first, figures of fiction later, that I learned how to be patient, to trust and to confide in time, that same time that simultaneously builds and destroys us in order to build and once more to destroy us.

. . . The Stone Raft—separated from the Continent the whole Iberian Peninsula and transformed it into a big floating island, moving of its own accord with no oars, no sails, no propellers, in a southerly direction, “a mass of stone and land, covered with cities, villages, rivers, woods, factories and bushes, arable land, with its people and animals,” on its way to a new Utopia: the cultural meeting of the Peninsular peoples with the peoples from the other side of the Atlantic, thereby defying—my strategy went that far—the suffocating rule exercised over that region by the United States of America . . . A vision twice Utopian would see this political fiction as a much more generous and human metaphor: that Europe, all of it, should move South to help balance the world, as compensation for its former and its present colonial abuses. That is, Europe at last as an ethical reference. The characters in The Stone Raft—two women, three men and a dog—continually travel through the Peninsula as it furrows the ocean. The world is changing and they know they have to find in themselves the new persons they will become (not to mention the dog, he is not like other dogs . . .).

. . . Blind. The apprentice thought, “we are blind,” and he sat down and wrote Blindness to remind those who might read it that we pervert reason when we humiliate life, that human dignity is insulted every day by the powerful of our world, that the universal lie has replaced the plural truths, that man stopped respecting himself when he lost the respect due to his fellow-creatures. Then the apprentice, as if trying to exorcise the monsters generated by the blindness of reason, started writing the simplest of all stories: one person is looking for another, because he has realised that life has nothing more important to demand from a human being. The book is called All the Names. Unwritten, all our names are there. The names of the living and the names of the dead.