Struggle and resistance in the work-place is more common than readers might think. If we think of resistance or conflict between capital and labour in work-places as only industrial disputes, well then, yes, it is a pretty dismal picture.

Of course we see the headline disputes of workers collectively organised in unions fighting for better pay, or better job security, or to protect working conditions. We have seen big disputes fought by such unions as Mandate, SIPTU and the NBRU over the last few years.

Struggle organised collectively and strategically by unions is the more advanced form of workers’ struggle, with most chance of success. But many other forms of resistance and struggle exist, which can often go unnoticed.

Every day all over this country workers resist, argue, make fun of, grouse about, take individual cases, march into the bosses’ offices, send e-mail, ignore instructions, sabotage, and much more, which are all forms of resistance or struggle. Because they tend not to make headlines, and because they are more often than not unorganised and non-union, it can create an illusion of workers having given up and accepted the status quo. This isn’t the case.

The conflict that exists in every work-place today is about the same core issues as it was a hundred years ago; it just takes place through different mediums of control. Bosses still want to maximise profits over wages; they still want to extend the working day as long as they can; and they still want workers to do more during the working day. This creates conflict in the work-place over (1) wages v. profits, (2) working time v. private (living or family) time, and (3) the speed or pressure of demands placed on workers during the day.

Wages

Most work-places now, certainly non-union ones, operate highly individualised, divisive performance-related pay structures, where workers are performance-rated against their colleagues and against objectives imposed on them by the management, and also benchmarked externally against “market” rates for the role they are in.

This is all done by Human Resources Departments behind closed doors and communicated to employees confidentially, not to be discussed. This is a mechanism of control over workers as well as control over wages.

But even in these situations of massive power imbalance, workers resist. They compare notes with their colleagues (breaching the confidentiality imposed on them). They may appeal their rating to try to get more out of it. They may start looking for work elsewhere. They may say “to hell with it” and slow down or reduce the quality of their work. They may lash their employer out of it on glass-door web sites. They may write graffiti on the toilet door.

Whatever the form, most workers don’t like the lack of control, and don’t like the imbalance in power between capital and labour in the work-place.

Working time

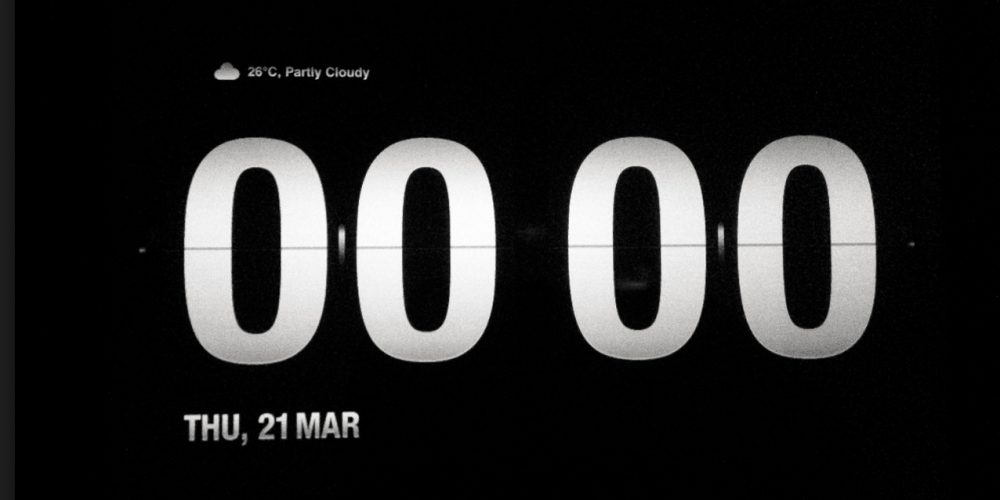

The conflict created over working time is on the rise and is increasingly quoted by employees in surveys as a major source of discontent. It is less the formal extension of the working day or working hours and more the informal staying late, coming in on weekends, or, most often, the logging in to iphones, tablets or laptops in the evenings to answer the constant flow of e-mail while trying to enjoy their free time or time with their families.

This encroachment into social or family time does lead to burn-out and may well be the health and safety issue of this decade for many workers. And employees do react. Unfortunately this form of extension of the day can be extremely pervasive, as employers offer the latest smartphones and devices to their staff, creating the conflicting tensions of flexibility and autonomy with captivity and enslavement in the workers’ life.

The most desperate reaction is for workers to “go sick” as a result of actual burn-out or just in a kind of “I’m as mad as hell and I’m not going to take it any more” moment.

Working demands

Not content with extending the day unpaid into personal time, employers increasingly demand more from workers during working time. Previously, and still for some occupations, this was done through speeding up an assembly line or process, but more frequently now this is done through “stretching” performance management objectives or changing the goalposts of one’s objectives.

For many workers in office or technology roles, performance management is the modern form of scientific management, through which employers monitor, measure, control and rate employees’ work. But again employees often rebel. They learn how to game the numerical systems, and do it. They appeal against unachievable objectives or unfair ratings.

These forms of resistance may often be individualised and uncoordinated, but they are resistance nonetheless. The conflict and struggle in the work-place hasn’t gone away, and unions must organise workers on the three main points of conflict: wages, working time, and labour process.